There are challenges to be found in the whole of Persia three weaves which differ more widely from each other than the three weaves of Persian Kurdistān: the Senneh (Senna) weave, the Bijār (Bidjar) weave, and the weave of the Kurdish tribal rugs. The first is carried on exclusively in the town of Senneh and the second in Bijār.

The 'Juive' Wife of a Kurdish Chieftain by Antoin Sevruguin (C. 1890-95)

The 'Juive' Wife of a Kurdish Chieftain by Antoin Sevruguin (C. 1890-95)In 1530, Ottoman pressure caused the Ardalans to move their people from their capital of Shahrazur (Sulaymania) eastward to the fortress of Dhelam on the borders between the Ottoman and Persian spheres of influence. In the seventeenth century, they made Senna, a mountain castle fortress, their capital. The province of Ardalan was 200 miles (320 km) long, north to south, and 160 miles (250 km) in breadth. In the south, it was divided by a small range of hills from the plain of Hamadan.

Senneh (Senna) became the capital of Persian Kurdistan sometime 200 years ago. Before that time, it was little more than a village, and the seat of government was in a castle five miles farther west. The ruins of the fortress can still be seen crowning an eminence that overlooks the village of Hassanabad. The astute Persian monarchs no doubt preferred to have their deputies reside in a locality that was easier to master than a castle planted on the top of a hill. The population of Senneh is estimated at 20,000. Except for the garrison, the government officials, and about a thousand Jews, the inhabitants are Gurāni Kurds. They are relatives of the great Gurāni tribe, whose territories lie farther south toward Kermanshah.

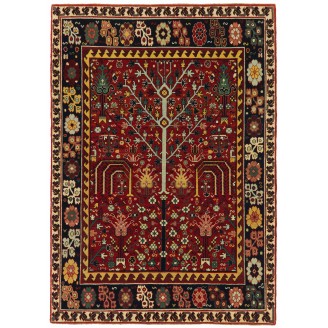

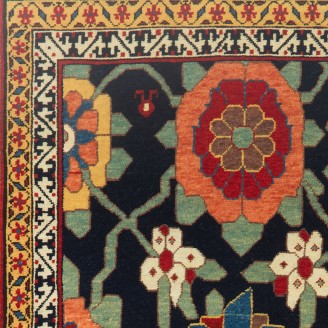

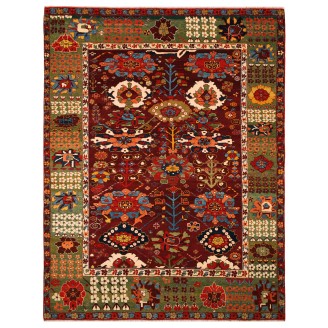

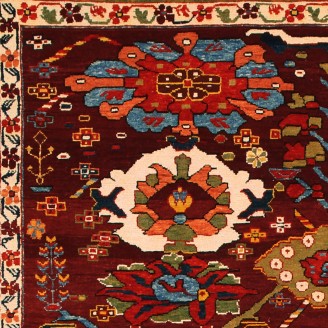

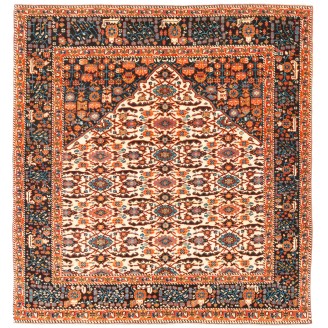

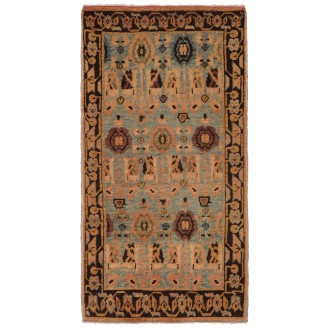

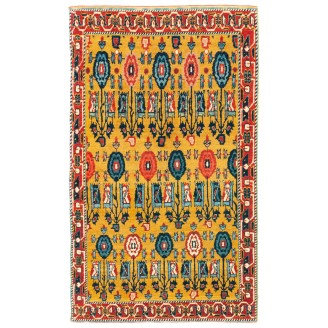

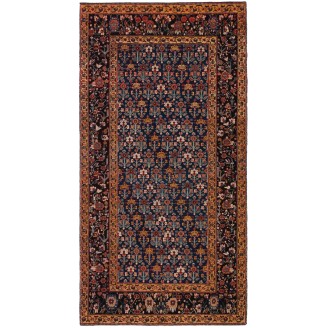

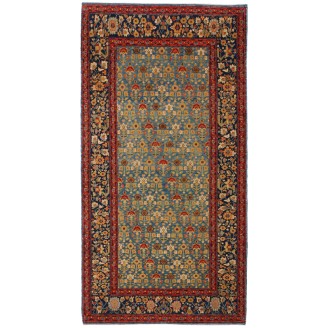

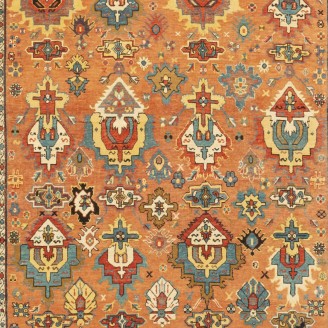

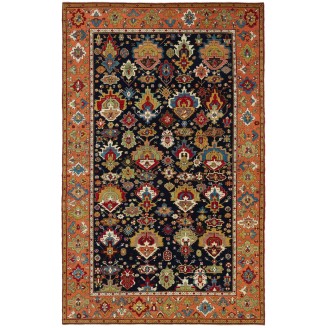

Senneh carpet differs significantly from that originating in any other part of Kurdistan, and, indeed, even the surrounding villages produce the typical crude Kurdish tribal weaves. The rugs of Senneh have a peculiar fascination. The best examples possess a refinement of texture, originality, and a naïveté in color and design, which are delightful and unsurpassed by any other Persian weave. They are also unique in style and unmistakable: none of the rugs of Persia remotely resemble them. The weavers of this remote little Kurdish town are among the few in Persia who have preserved a style and dignity of their own. For 200 years, they have continued to weave in their way, undisturbed by the whims and fashions of the West.

Throughout the nineteenth century, fine carpets and textiles continued to be woven in Senna for the aristocracy and the rich of Persia; they were also exported to Europe and North America. In the nineteenth century, the Senna designers generally employed a Persian-inspired curvilinear motif that emulated Safavid medallion book cover designs and the popular nineteenth-century Boteh designs, or they used the traditional Kurdish Masi Awita and Mina Khani designs.

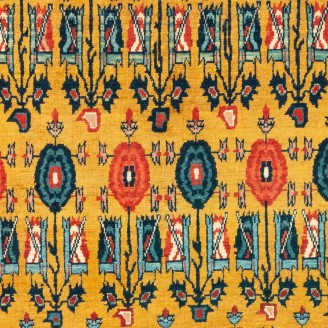

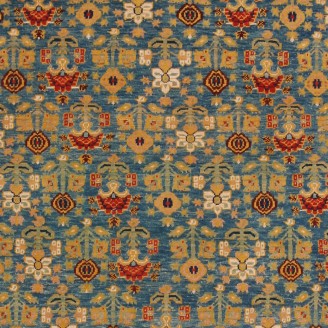

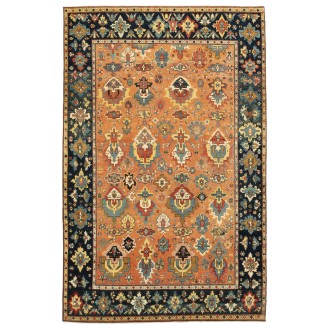

Senna Patterns

Senna PatternsThe carpets of Senneh are among the most finely woven of all Persian rugs, with knot counts running as high as four hundred (which is probably as fine as we will ever find with the Turkish knot) and seldom below one hundred and twenty. The pile is closely clipped. The foundations are wool; the weft crosses only once, unlike the usual Kurdish practice. The result is a thin fabric with a characteristic rough feel on the back, which is distinctive enough to identify the blindfolded rug.

These weavings have a thin foundation with close-clipped symmetrical knots. The backs of these rugs feel “scratchy” to the touch, which is an identifiable characteristic. Starting in at least the early nineteenth century, perhaps earlier, and continuing throughout the twentieth century, they were single-wefted with a cotton (sometimes silk) weft and warp.

Photo: Senna Rug Weaving, 2021 Celikhan

Photo: Senna Rug Weaving, 2021 Celikhan