Turkish Court Manufactury Rugs were woven in the Egyptian workshops founded by Ottoman Empire in the 16th century. Those carpets were woven in Egypt, following the paper cartoons probably created in Istanbul and sent to Cairo then.

Photo of 'Young Lady at Dolmabahce Palace' 19th Century

Photo of 'Young Lady at Dolmabahce Palace' 19th Century

'Saz'-Style Drawing of a Dragon Amid Foliage, Shah Quli, ca. 1540–50, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

'Saz'-Style Drawing of a Dragon Amid Foliage, Shah Quli, ca. 1540–50, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkShortly after its conquest by the Osmanli Turks (1517), a change of style was set in Egypt which, due to the establishment of a manufactory working for the court in Istanbul, found a powerful expression in the carpet industry.

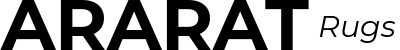

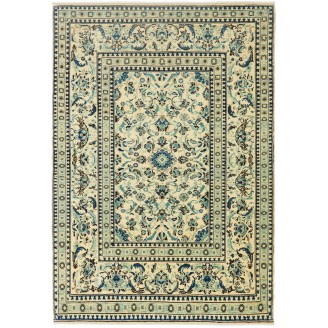

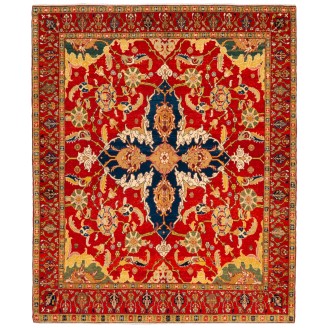

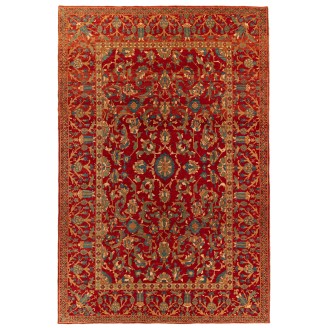

While the weaving of carpets in the traditional geometric Mamluk designs continued well into the seventeenth century, sometime around the mid-sixteenth century, Cairene weavers began to create an entirely new kind of carpet, using their traditional Mamluk materials, technique, and coloration but reflecting the latest styles then being made at the court of the Ottoman sultans in Istanbul.

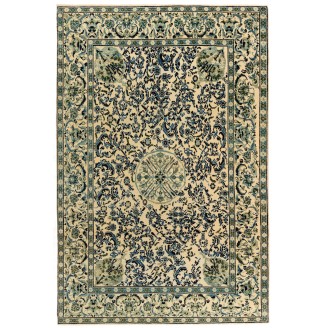

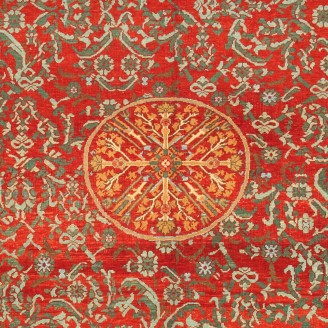

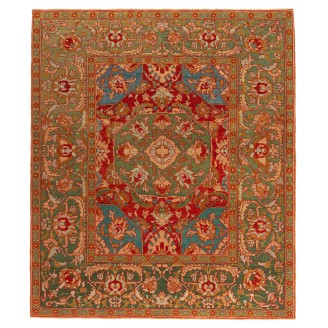

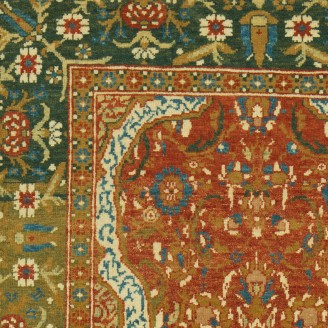

A splendid example of this new Ottoman court weaving, the Blumenthal Carpet, shows us the characteristics of the latest style. The carpet was woven following a paper cartoon probably created in Istanbul and sent to Cairo. Therefore, the field design is repetitive on a relatively small scale (not unlike the small-pattern Holbein) and follows the concept of an infinitely repeating pattern cut by the border, as in the Star Ushak medallion carpet. However, the curvilinear designs, consisting of small round metal lions, sprays of flowers, and curved, feather-like serrated (saz-style) leaves, echo the court style of faraway Istanbul, originating in the pen-on-paper designs of the famous court artist Shah Qulu.

As time passed and royal commissions from Istanbul came more infrequently, Cairene weavers turned to producing carpets in both new and old styles for export to Europe, where, from time to time, European painters documented such carpets in their depictions of European nobility.

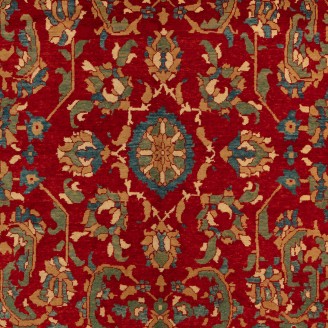

Carnations, tulips, hyacinths, lilies, peonies, and other flowers, together with gracefully sweeping lancet leaves, sumptuous palmettes, and delicate sprays of blossoms, constitute the rich flora of these carpets, whose borders charm the eye with their elegant solutions for the corner problem, while in the guard stripes almost invariably little rosette-flowers appear all in a row. It is merely by way of exception that we will still find appropriations levied upon the Mamluk tradition. On the other hand, the coming revolution in decor is already heralded in a few specimens that we still count as belonging to the earlier group. In pure folk art, such a radical overturn would be quite inconceivable. Still, in the operation of a manufacturer, the introduction of a completely novel program can be accomplished with a minimum of confusion. With this change of orientation, it was significant that the idea of a governing medallion, even with a different conception, had already been used.

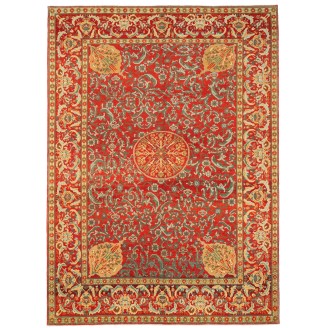

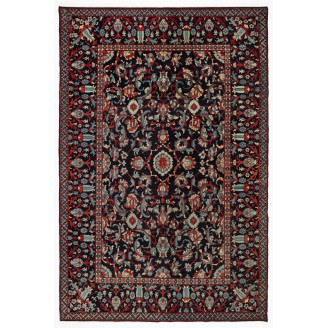

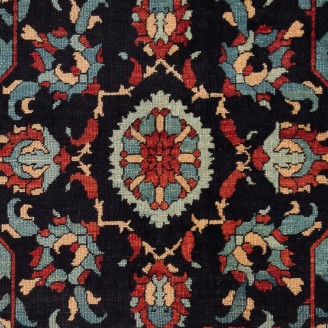

Ottoman Rug Patterns

Ottoman Rug Patterns Blumenthal Carpet, 17th century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Blumenthal Carpet, 17th century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkThe Cairene Ottoman carpets correspond with those of the previous period both in material and in color range, and the palette is extended only through the more plentiful use of yellow, white, and a few other tints; occasionally, however, they were inclined to be satisfied with the three Cairene basic colors. Nevertheless, if doubts have been expressed regarding the continuity of their production, these were based entirely on the fact that the new rugs renounced completely the decorative orientation that had been observed up to that point. Vegetation, which at times is naturalistic, at times stylized peculiarly, is deployed luxuriantly and, in forms that are known to us from Turkish wall tiles and brocades, quite fills the field in endless continuation, interrupted by a large or a small medallion, quadrants of which are often repeated in the corners.

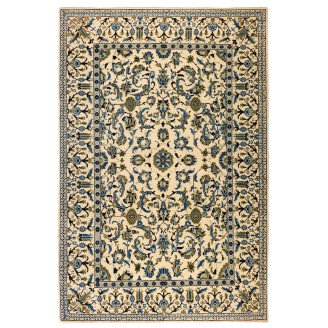

We can surmise that the designs and colors of Mamluk carpets, with their unusual combination of insect-derived red, blue, green, and sometimes yellow, with virtually no undyed white at all, constitute an effort to create a recognizable brand in the early modern market, especially in Europe, where Mamluk carpets such as this, with their subtle coloration, incredibly detailed design, and mosaic-like layout of small and intricately patterned geometric motifs, constituted an appealing alternative to the more coarsely woven and brightly colored carpets from Anatolia, such as Ushak medallion carpets.

Attempting to read early carpets produced in workshops in Cairo provides an entirely different set of challenges. Cairene carpets are distinguished by their limited color palette, symmetrical knotting, and unusual construction of S-spun wool. A new carpet genre instigated a hybrid structure, crossing the Persian knot with depressed warp and three-weft shoots with the all-woolen build of Anatolia. Why they employed woolen warps, not cotton, is a mystery: only these carpets employ a 4-ply woolen warp. The weft is also eccentric: a multiple, non-plied yarn, sometimes used in Turkmen carpets. In general, the Mamluk carpets have a square weave, facilitating the transfer of geometric designs. So characteristic is the S (and SZ) spinning that it must be considered integral to a design concept of exorbitant symmetry.

Photo: Ottoman Rug Weaving, 2020 Diyarbakir

Photo: Ottoman Rug Weaving, 2020 Diyarbakir