The Renaissance of Islamic Art. From the time of the Prophet Muhammad until today, Islam has represented a way of life, an all-encompassing approach to life itself. The era’s dedication to the philosophy and message of Islam is mirrored in its art, which is predominantly ordered, symmetrical, and geometric in conception and execution.

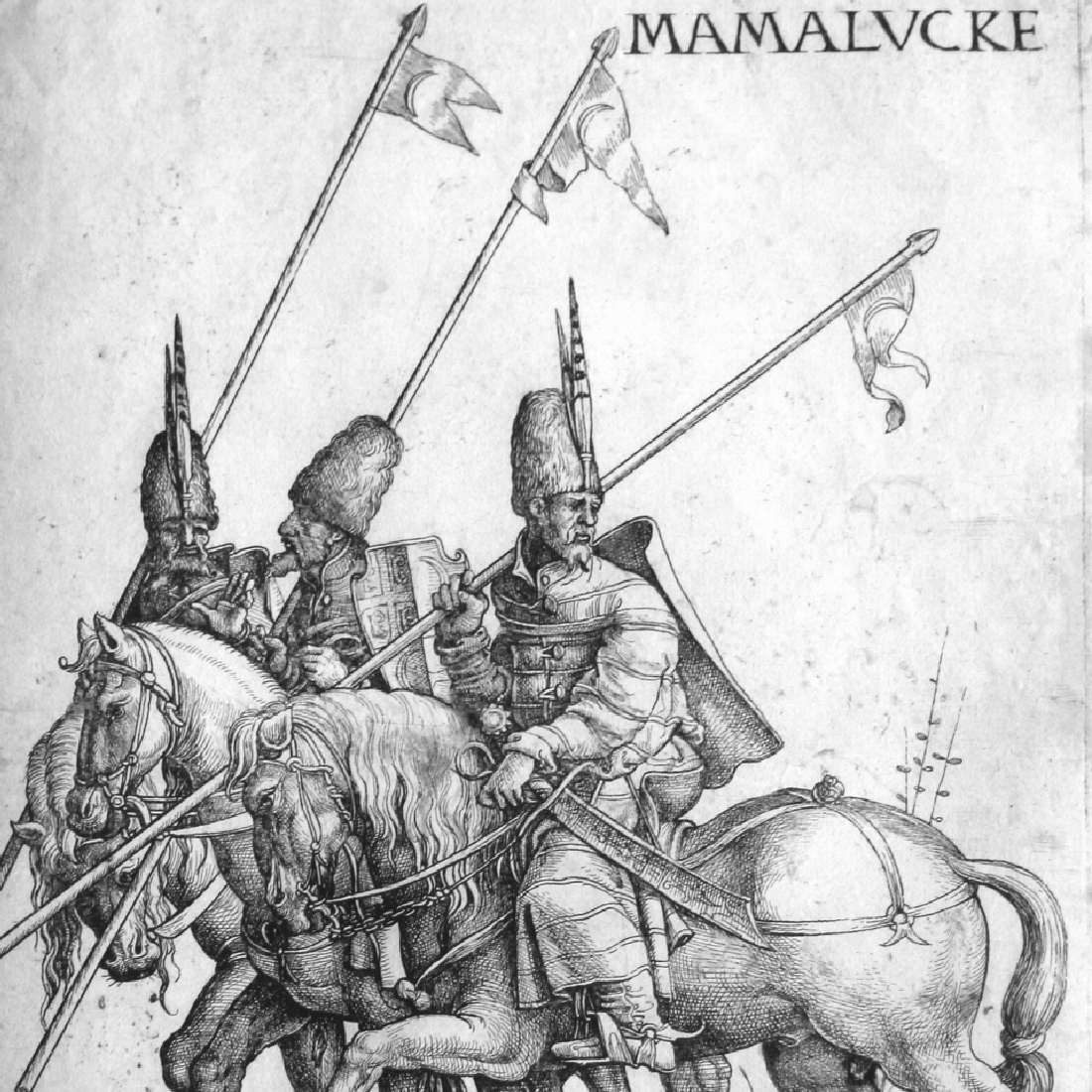

Photo: Three Mamelukes with Lances on Horseback

Photo: Three Mamelukes with Lances on HorsebackWhy does a society blossom in a bouquet of artistry at a given moment? Such a moment occurred when the Mamluk sultans, based in Cairo, ruled the East from the mountains of Turkey to the sands of Nubia, from the eastern shores of the Mediterranean to the Arabian Sea.

By Western reckoning, the period was that of the Middle Ages. For the world of Islam, the two hundred and fifty years of Mamluk rule have marked a rebirth, a renaissance. Yet there were parallels between the West and East regarding human goals and achievements. As the workers, peasants, and merchants of medieval Europe thrust their Gothic spires toward heaven, the artisans of the Arab East expressed their faith and societal concepts with achievements of architecture, religious manuscripts, metalwork, and glass, which form a legacy of luxury and beauty.

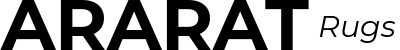

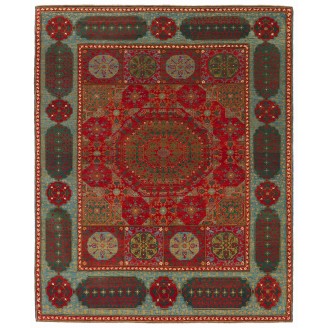

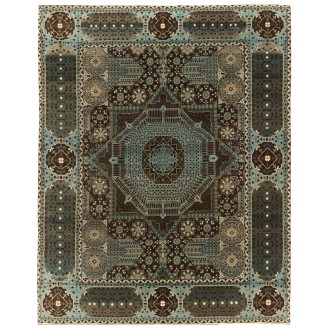

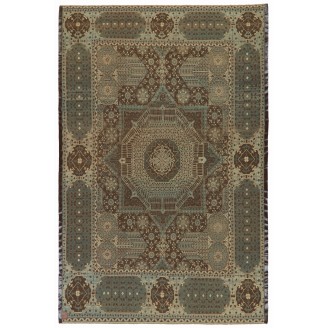

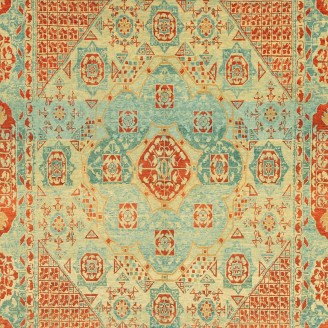

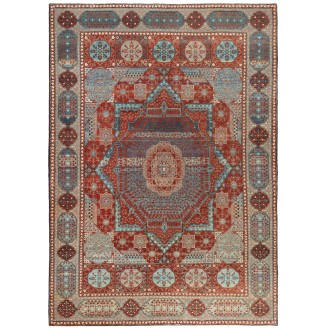

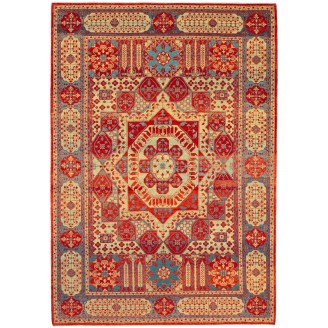

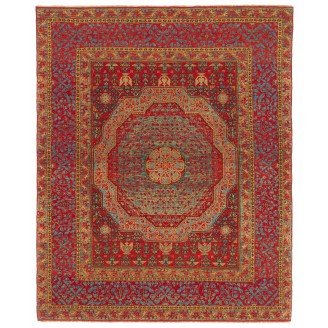

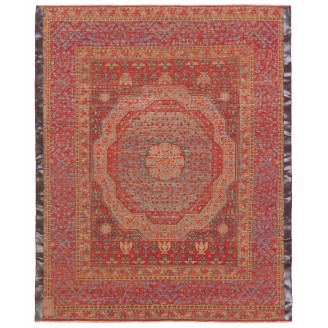

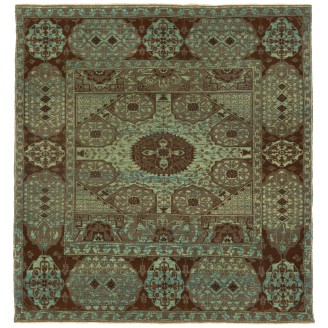

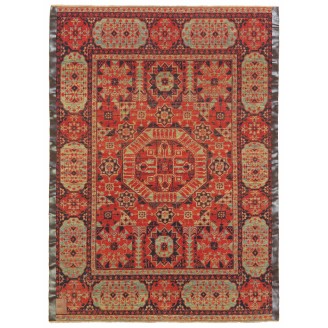

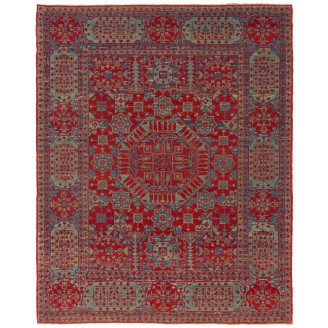

The design of the rugs is unique to the Mamluk world, consisting of a square that is transformed into a rectangle by adding two oblong panels. This rectangular component is either single and framed by a wide border or triple, in which case the central square is more prominent, and a border encloses all three units. The only exception is the celebrated five-partite rug the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York owns.

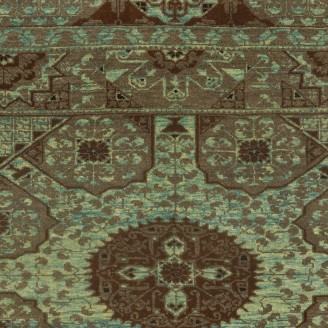

The decoration of the central square utilizes geometric units radiating from the center. The core is often a multipetaled rosette enclosed by a star within a medallion. The encircling zones grow larger as they open out from the core, forming a series of stars, hexagons, octagons, and polygons, each subdivided and decorated in contrasting colors with alternating motifs. The overall kaleidoscopic effect is similar to the cosmic compositions of manuscript illumination, woodwork, and inlaid stone. The oblong panels flanking the central square are either tripartite, their components echoing the central design, or contain rows of stylized cypresses, palm trees, papyrus sprays, abstracted florals, and arabesques. The border often consists of medallions alternating with oval cartouches; some later examples have overall floral patterns in the borders.

Mamluk Patterns

Mamluk Patterns The Last Supper, 16th century, by Ambrosius Francken. Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp

The Last Supper, 16th century, by Ambrosius Francken. Royal Museum of Fine Arts, AntwerpThe Mamluk rug is the most striking of all Islamic carpets, woven in jewellike tones of red, green, and blue, with an almost silky iridescence.

With their limited color palette, the Mamluk carpet colors could easily have been dyed onto naturally colored light brown, beige, or grey wool. Even a decent yellow can be produced on beige wool if the pigment is intense enough. To dye yellow, both Luteolin (Weld) and Isparek (Delphinium semibarbatum) were employed, often combined with Dyers Sumach (Fisetin) for added durability. The Persian Isparek may have been grown locally. Mamluks controlled the Spice Route. Indigo was cultivated in Egypt. The Mamluk carpet remains tricolor, consistent in wool, dyes, and weaves for at least a hundred years.

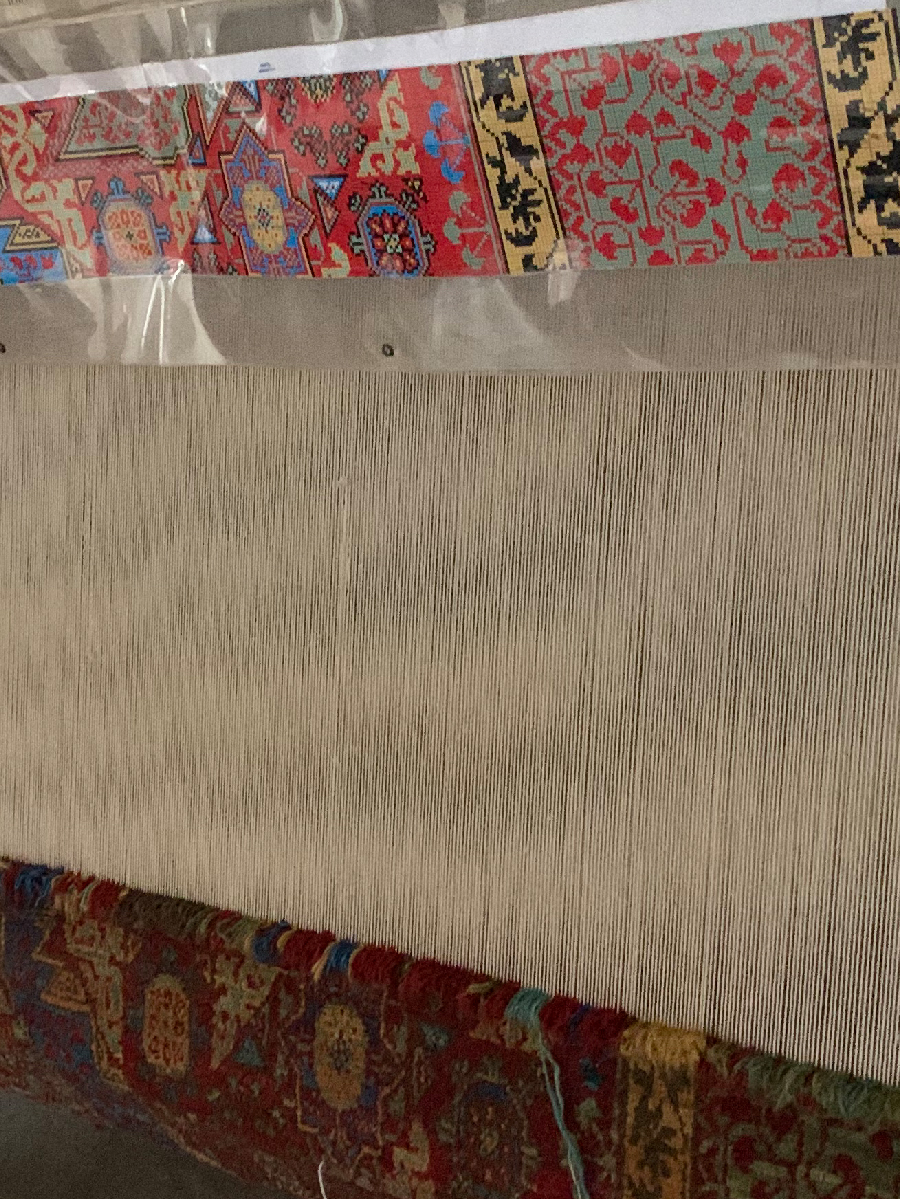

A new carpet genre instigated a hybrid structure, crossing the Persian knot with depressed warp and three-weft shoots with the all-woolen build of Anatolia. Why they employed woolen warps, not cotton, is a mystery: only these carpets employ a 4-ply woolen warp. The weft is also eccentric: a multiple, non-plied yarn, sometimes used in Turkmen carpets. In general, the Mamluk carpets have a square weave, facilitating the transfer of geometric designs. So characteristic is the S (and SZ) spinning that it must be considered integral to a design concept of exorbitant symmetry.

Photo: Mamlouk Rug Weaving, 2020 Diyarbakir

Photo: Mamlouk Rug Weaving, 2020 Diyarbakir