Kirman (Kerman) is one of the significant rug-producing areas of Persia. It has probably had a less eventful existence than any other center of comparable size, and the arts have been allowed to flourish and expand with relatively little interference from the outside. This can be accounted for by its geographical isolation, which kept the city outside of the usual commercial channels (except for the ancient caravan route to India, which decreased in importance as the sea routes were opened) and the arid climate that has made Kerman the poorest of the five significant provinces of Persia.

Mercator Map of Carmania (Kirman) c.1578 Asiae Tabula IX

Mercator Map of Carmania (Kirman) c.1578 Asiae Tabula IX

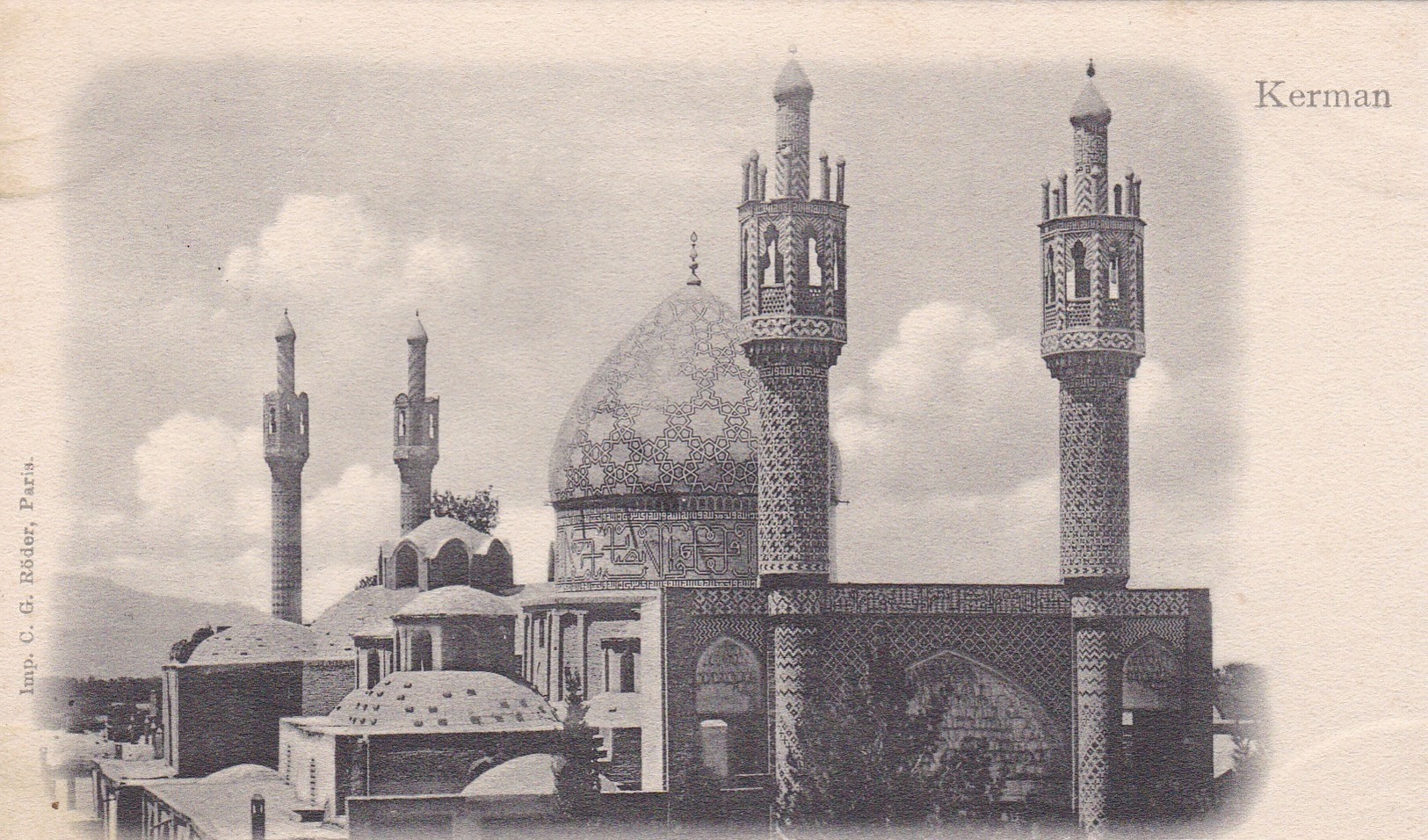

Kerman Mosque, 19th Century Photo Postcard

Kerman Mosque, 19th Century Photo PostcardCarmania (Greek: Καρμανία, Karmanía, Old Persian: Karmanā, Middle Persian: Kirmān) is a historical region that approximately corresponds to the modern Iranian province of Kerman, and was a province of the Achaemenid, Seleucid, Arsacid, and Sasanian Empire. The region bordered Persia in the west, Gedrosia in the southeast, Parthia in the north (later known as Abarshahr), and Aria to the northeast. Carmania was considered part of Ariana. The city existed for centuries in provincial isolation, with its basic Persian population little disturbed by the repeated invasions that devastated other parts of the country. The Seljuks, conquerors of the area in the eleventh century, showed no desire to settle there, as they did in Azerbaijan and Hamadan, and the Mongols did not venture that far south. There was little incentive for them to do so, as Kerman was not wealthy. Under the Safavids, the province enjoyed undisturbed tranquility, and even the Afghan invasion was not a disruptive factor. The only major siege of the city occurred in 1794, and the army of Aga Mohammed Qajar did considerable damage. The city slowly recovered but remained relatively poor. In more recent times, it has been important almost exclusively as a carpet center, entering only peripherally into the political and social movements that have brought about much change in Persia.

The development of the carpet industry is poorly documented in Kerman, as elsewhere, although we have clear documentation that weaving occurred during Safavid's times. Some of the best wool in Persia- soft, white wool- is produced in Kerman; there were such limited opportunities for attracting money from the outside that turning the wool into a medium of exchange was virtually inevitable. Kerman fabrics of various types have thus developed to meet the prevailing styles demanded by commerce. In Marco Polo's day, the fabrics were not rugs, as he does not mention them while describing other types of cloth in detail. Chardin, who was in Kerman in 1666 and 1672, describes local carpets, as did the chronicle of Shah Abbas, the "Alamara-i-Abbasi." Carpets were shipped from Kerman to India during this time, and quite possibly, they influenced the weaving of that country. We do not know the Afghan invasion's effect on Kerman's industry, but we may surmise that it induced a decline. Still, carpet weaving must have continued at some level during the eighteenth century.

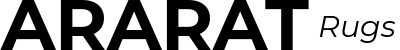

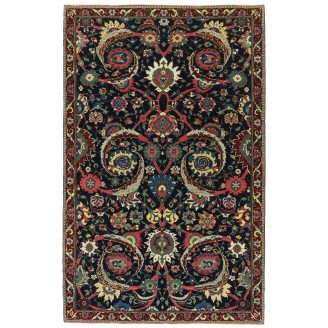

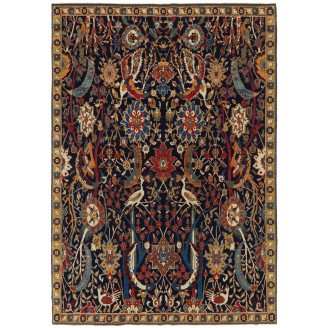

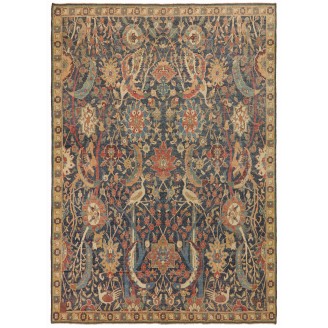

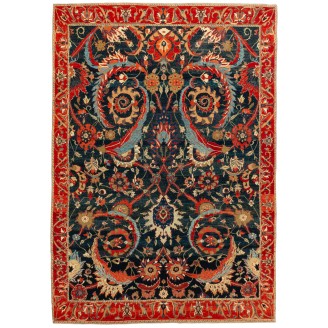

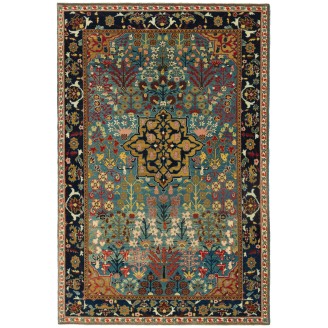

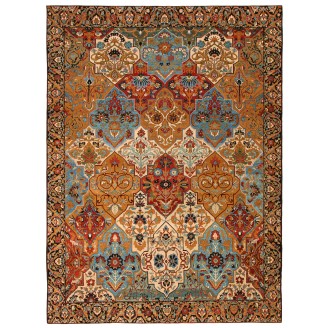

Much could be said to praise the design of Kerman rugs. Consistently, from the 1870s through the 1930s, the Kerman was exquisitely conceived and executed, with a more thorough design development than one finds elsewhere. Many of the finest rugs involved elaborate overall or panel designs, and there were many adaptations from various shawl patterns. The designers were encouraged to be inventive by their status in the city; they were among the most respected local artisans. They have probably contributed more to the art than all designers from the rest of the country combined, and many of the best from Kerman were enlisted in the founding of the Institute of Design in Tehran. While individual rugs of other cities might be more appealing than the finest Kermans, the general level of excellence has been unapproached.

In pattern, the carpets are distinguishable from those of the North and West by this purity of color and a greater boldness and originality of design, probably due to a slighter infusion of Arab prejudices on the representation of living forms. Flowers, trees, birds, beasts, landscapes, and even human figures are found on the Kerman carpets.

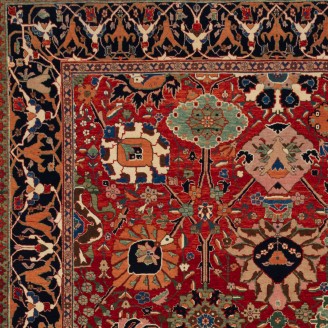

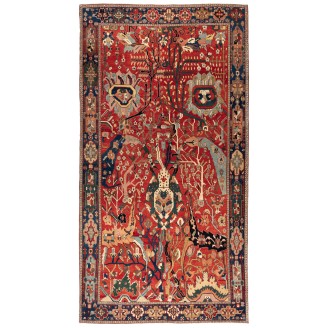

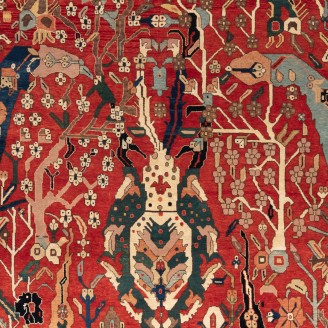

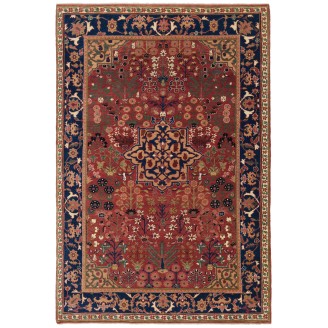

Kirman Patterns

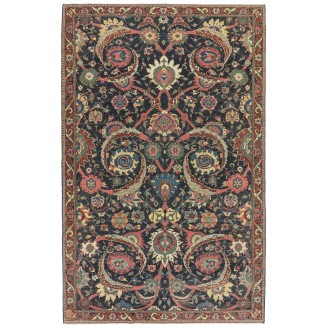

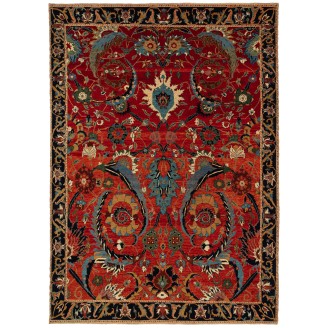

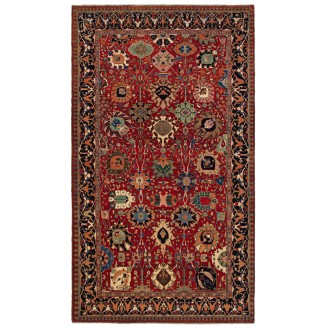

Kirman Patterns Kerman Vase Technique Rug, The Most Expensive Rug Sold at Auction (33m. USD), Sold on June 5th, 2013 at Sotheby’s Auction in NYC

Kerman Vase Technique Rug, The Most Expensive Rug Sold at Auction (33m. USD), Sold on June 5th, 2013 at Sotheby’s Auction in NYCThe white wool of the Kerman sheep, added perhaps to some quality of the water, gives brilliance to the coloring unobtainable elsewhere.

The dyes of Kerman are probably the most varied and imaginative in all of Persia. The number of shades available is enormous, and one may find considerable variation within one rug. Cochineal has traditionally been used for the reds, with only a subsidiary use of madder. This provides shades from the most delicate pink to a deep magenta and is characteristic of the Kerman carpet, just as deeper shades of the same dye are associated with the works of Mashad. The blues are from indigo, and again, various shades are available. Synthetic dyes have done less well in Kerman, probably because the dyers have been important artisans.

The rugs of Kerman have always been among the most easily recognized fabrics of Persia, with curvilinear, graceful floral designs in a brilliant variety of colors. They have been woven in virtually all sizes up to the largest carpets, with a size of about 4 x 6 feet being the most common and probably the one eliciting the most exquisite artistry. The foundation is always cotton, differing from other Persian city rugs in that there are three wefts between each row of knots, one of which is exceedingly thin. (This does not strengthen the fabric but is a matter of tradition.) Alternate warps are depressed, while the pile is short on the older specimens. Kermans have at least four grades of knot density, with the finest over 18 x 18 to the inch and the others counting approximately 16 x 16, 14 x 14, and 12 x 12. The Kerman virtually always has over 140 knots to the inch.

Photo: Kirman Rug Weaving, 2021 Diyarbakir

Photo: Kirman Rug Weaving, 2021 Diyarbakir