Located in east Azerbaijan, about one hour’s drive from Tabriz to the northeast, it is one of Persia’s most untouched weaving areas. We call it the Heriz area, but it might be named, with almost equal propriety, the Georavān, the Mehriban, or the Bakshaish area. Rugs bearing the names of these and other villages were daily trafficked in the Tabriz bazaar.

The rug trade in Genje (Elisabethpol), Azerbaijan, in the late 19th century.

The rug trade in Genje (Elisabethpol), Azerbaijan, in the late 19th century.Weaving has been carried on in the Heriz area certainly since the beginning of the nineteenth century; Bakshaish is the village where weaving has been going on the longest, now producing the region’s characteristic carpet, but which in the late nineteenth century had a tradition of weaving carpets similar in design to those of Arak. The typical Bakshaish was identical to the so-called Ferahan of the time, with an overall Herati pattern, usually a more squarish shape than the narrow Ferahans. They are double-wefted and Turkish knotted, differing from the Arak pieces.

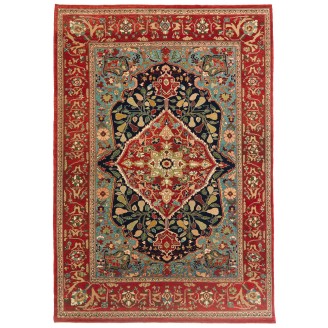

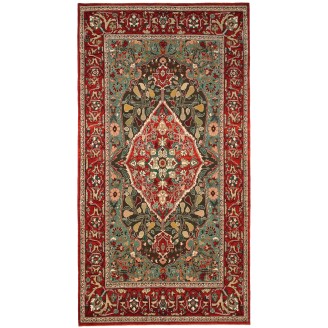

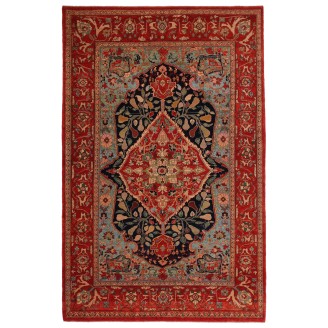

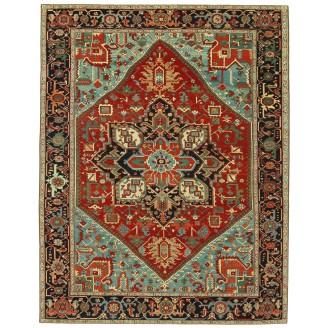

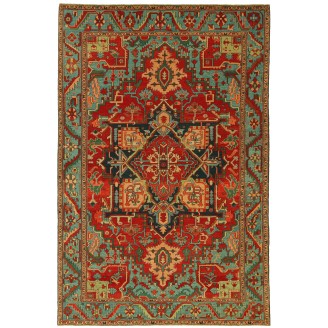

The Tabriz merchants knew that the West demanded carpet sizes in medallion designs instead of the long and narrow pieces in small repeating patterns the village weavers had previously been producing. It was in the course of things, therefore, that one of those enterprising traders should send to Georavān (at that time a significant village) or to Bakshaish or Herīz an ordinary, curvilinear medallion-and-corner Tabriz design to see what the village weavers would make of it. And then, of course, the inevitable happened: the weavers of the area (as incapable then as they are today of weaving curves) broke up the design into straight lines vertical, horizontal, and diagonal 45 degrees and thus, unwittingly, produced the Heriz or Georavān design.

Until recent years, the weavers of the Heriz area procured their wools or spun yarn from the neighboring Shah-seven tribes. That admirable practice is, unhappily, fast disappearing. Today, the villagers buy their yarn ready to be spun in the bazaars of Tabriz or Ardebil.

These rugs are renowned for their rectilinear designs, a feature unusual in Iran, where the traditional prefer the arabesques and scrolls so typical of Persian manufactory rugs. This feature has been explained by some authorities who are at pains to assert that the Heriz weavers are incapable of weaving anything other than straight lines. However, even a cursory examination of some of the masterpieces from the looms of Heriz will dispel any belief that their weaving capabilities are limited. The more likely explanation is that they prefer the rectilinear style, which has proved successful in foreign markets for over a hundred years.

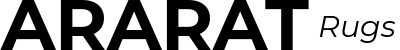

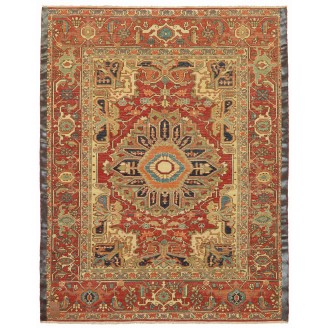

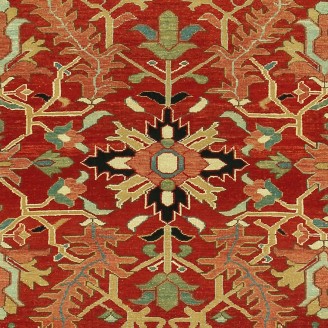

Heriz Patterns

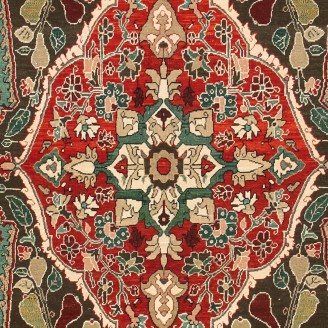

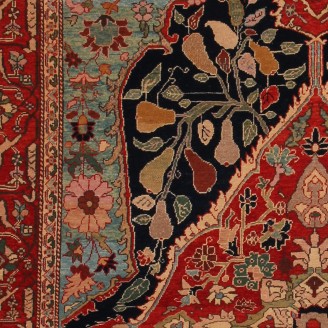

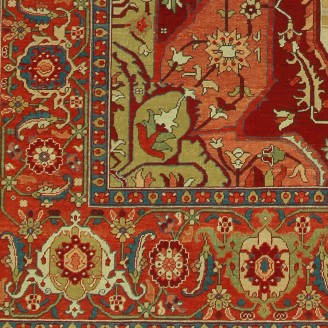

Heriz Patterns Quarter of our Heriz rug

Quarter of our Heriz rugNorthwest Persian rugs mostly used similar colors, but Heriz has a particular red and light blue. Until the last decade, the yarns were dyed in the villages; the blue, red, and green by the village dyers, the other shades by the weaver herself in her pots over her fire. Both used the excellent, time-honored technique of their ancestors. Late in that time, the blue, red, and green were dyed in Tabriz with synthetic dyes by the town dyers. The use of natural madder, which for fifty years was the fabulous color in the carpets from the Heriz area, disappeared.

As Ararat Rugs, we have a unique red for Heriz rugs, which we buy madder roots from the city of Yazd.

Until recent years, the weavers of the Heriz area procured their wools or spun yarn from the neighboring Shah- seven tribes, long in the fiber, lustrous and lofty, and when dyed, it gave a clear, bright shade. The population is exclusively Turkish, and like all design and crude weavers of the Turkish race, they weave the Turkish ways.

Photo: Heriz Rug Weaving, 2021 Diyarbakir

Photo: Heriz Rug Weaving, 2021 Diyarbakir