Bijar (Bidjar or Bîcar) is a Kurdish town in North West Persia. There are nearly 40 villages around the city called the Bijar area. With an elevation of 1,940 meters, Bijar has been named the Roof of Iran.

Jean-Léon Gérôme - The Carpet Merchant

Jean-Léon Gérôme - The Carpet MerchantThe city was mentioned in the 15th century as a village belonging to Shah Ismail, the first ruler of the Safavid dynasty; Bijar became a town during the 19th century. During World War I, it was besieged and occupied by Russian, British, and Ottoman troops who, with the aid of the 1918 famine, halved the pre-war population of 20,000. At the same time, the weaving area of Bijar comprises the town itself and about forty villages within a radius of 30 miles.

In the fifteenth century, Bijār was a village, the property, it is said, of Shah Ismail, the first Sefavi monarch. About a century ago, its inhabitants had acquired sufficient wealth, and the consequence of gaining possession of their land and house in Persia was the mark of emancipation. Bijār became a town. Its geographical position, however, was not such as to make it a commercial center. It remained a market town of agricultural area of no particular importance.

Of all the towns of western Persia that were fought over and occupied by the opposing armies during World War I, Bijar suffered the most. The Russians first occupied it. But the Russians did not remain: they retreated before the pressure of the Turkish armies, and the Turks occupied the town. The hapless population was then subjected to Turkish retribution for alleged cooperation with the Russians.

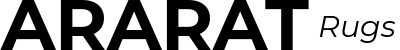

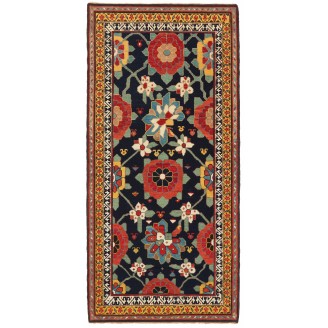

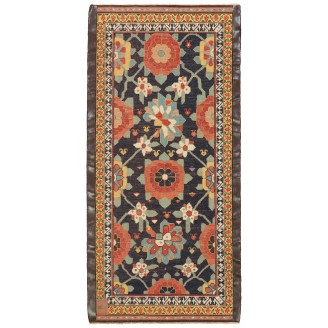

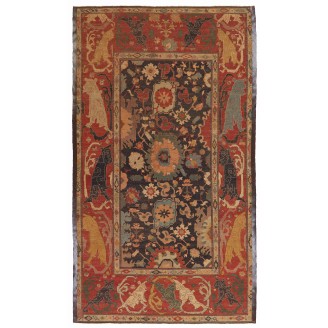

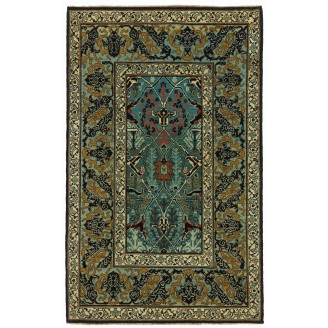

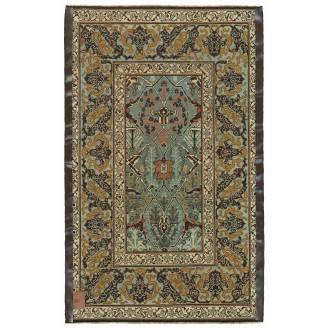

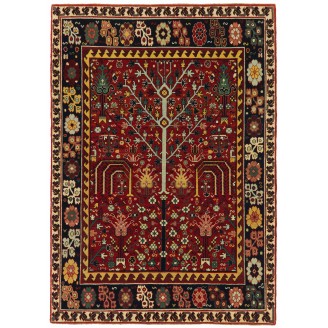

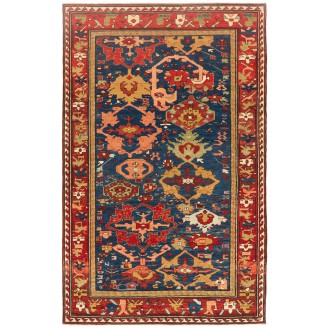

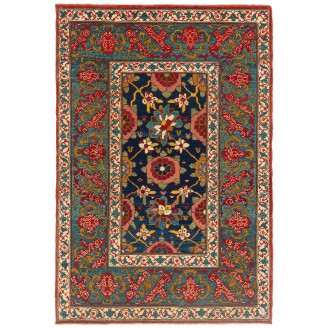

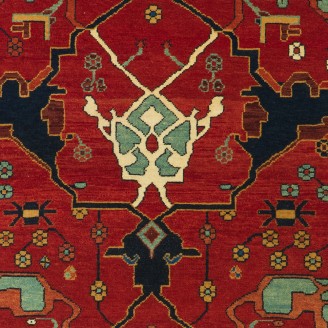

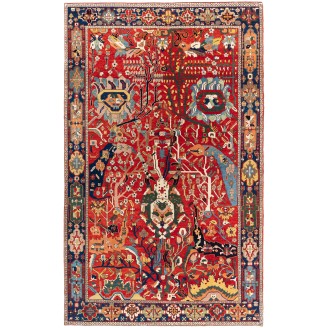

The designs of Bijār have always been few, simple, and generally rectilinear. The professional designer was an honored community member in places like Tabriz and Kashān; above all, Kerman was unknown in Bijār. Formerly, a design was associated with a particular village which was well known by the villagers and invariably woven there. In the introduction of the Wagireh system, a mat was woven, which showed one repeat of the design and was used as a sample pattern. The weaver enabled the merchants to distribute better designs more widely. The more recent introduction of scale-paper patterns has still further simplified the distribution. Nevertheless, the few Bijār carpets which are being woven today are lacking in a variety of designs.

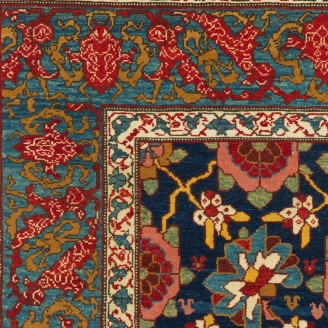

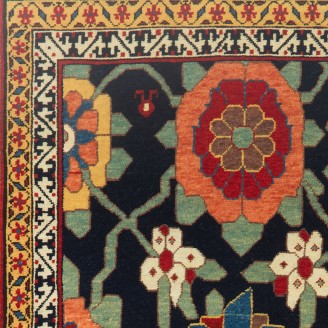

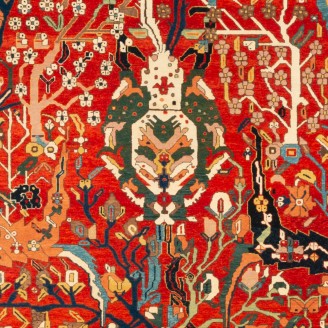

The motifs are mainly floral adaptations of classical Persian designs. Herati and boteh motifs, as are central medallions and sometimes representations of animals and willows, are common. These are set against a dark blue, red, or green background. About the size of the carpet, borders are small, with up to eight bands. The Herātī pattern in the overall design is also typical. But even that simple pattern was often mutilated by the inexperience or indifference of the weavers.

Bidjar Patterns

Bidjar PatternsBidjar carpets have stiff and heavy wool foundations created by “wet weaving” and beating the threads with a unique metal tool. Bijar carpets are famously stronger and longer-lasting than any others. They are made by Kurdish women in the villages around the town. The loom is set vertically against the side of the house. The designs have solid and clear colors and have never been out of fashion with overseas buyers.

They are inevitably heavy, inflexible, and have dense characteristics. After each row of knots has been completed, sometimes a tree or weft shoots are heavily beaten down. The high tension weft is often only spun or very loosely plied, as well as being very tick. This technique produces a highly compact construction. We do apply some water to the moisture weft to be able to beat them down yet harder.

Photo: Bidjar Rug Weaving, 2020 Adiyaman

Photo: Bidjar Rug Weaving, 2020 Adiyaman