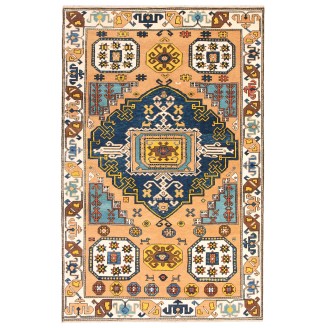

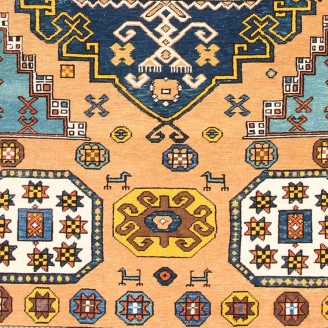

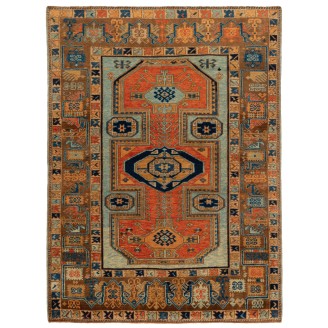

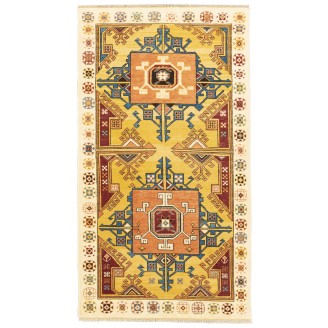

Anatolian rugs such as those illustrated in our collection are often referred to as 'village' rugs. However, it is more likely that most, if not all, of the carpets made in central and eastern Anatolia before circa 1550 were produced by nomadic tribes, probably small family groups who migrated between seasonal pasturelands with no regard for any notional boundaries that the authorities may have wished to impose. Although the Ottomans began to settle the Turkmen nomads of western Anatolia into towns and villages from the 1380s onwards, it was not until the mid-16th century that they made a concerted effort to settle some of the tribal groups in central and eastern Anatolia. Even then, many nomads were extremely reluctant to change their traditional way of life, and as late as the 1960s, small rug-making tribal groups were still wandering across Anatolia.

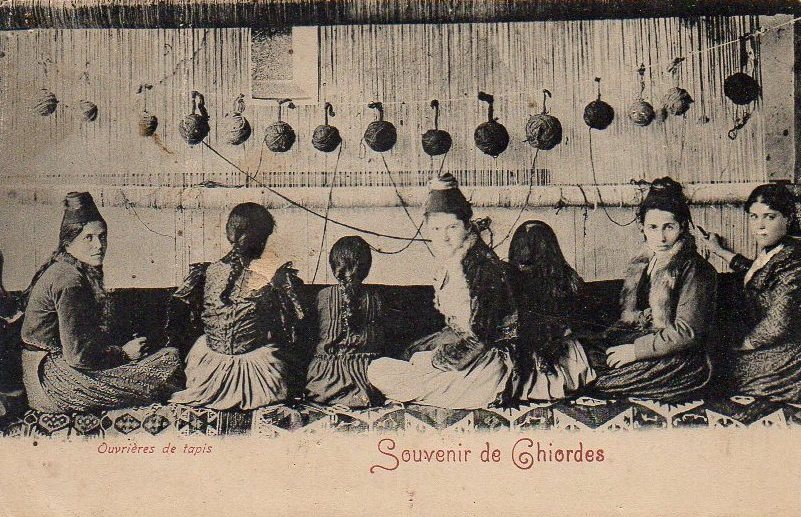

Turkish (roller beam) loom and weavers, c1900s

Turkish (roller beam) loom and weavers, c1900s

Turkish (roller beam) loom and weavers, c.1900s, Ghiordes Anatolia

Turkish (roller beam) loom and weavers, c.1900s, Ghiordes AnatoliaFrom 1048 onwards, in the wake of the Seljuk conquest, clans of Oguz Turkmen arrived from the mountainous Caucasus and the desert oases of modern Turkmenistan to feed their flocks on the abundant grasslands. The lure of the pastures was not the only cause of this migration. These centuries saw successive invasions, the destruction of settlements, and the intermittent lack of coordinated governance, especially in eastern Anatolia. The Mongol incursions of the mid-13th century precipitated a westward movement of the Turkmen people, as did Timur's subsequent invasion of Anatolia in the 15th century. These events were followed by the fractured period of beylik rule (numerous individual principalities governed by a local bey or lord) before establishing Ottoman hegemony, which was not without periods of disruption.

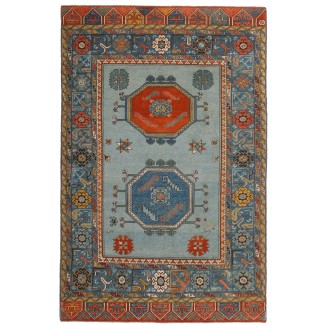

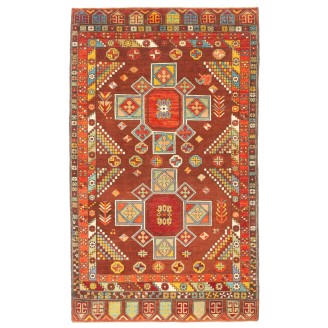

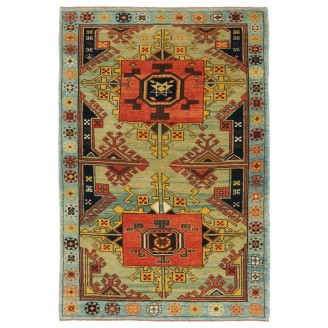

The carpets represent a perfect cross-section of the art of the tribal peoples of Anatolia from the time of the first migrations of Turkic peoples into this region until the 18th century. By the middle of that century, many of the small family groups who for centuries had woven knotted-pile carpets for their use had gradually settled into village life, with some making rugs commercially. The history of these family groups has been insufficiently studied; their movements within Anatolia and their role in society are left unaddressed, mainly due to a lack of written source material. It is not a new idea that the history of nomadic communities has suffered because of a readiness (on the part of both contemporary sources and later historians) to ascribe to them a two-dimensional role as the enemies of settled economy and culture. A certain bias also comes to bear in carpet scholarship in the supposition that the best carpets could have been woven only in settled Village communities and within a commercial context. By looking again at the historical context of Turkmen nomads in Anatolia from their arrival up to the 18th century, new possibilities emerge regarding the production of carpets in this period.

The compositions, patterns, and ornaments did not belong to the individual. Still, they formed part of traditional art passed on from generation to generation, as their mothers, grandmothers, and aunts guided young women. Once married, the young bride would leave her parents and often move away, and so the transmission of ornament may well have been through the maternal line alone.

Ethnographers report that textiles, which include carpets and kilims, were predominantly made by a bride for her dowry. Apart from her ability to make strong weavings that would last at least fifty years, the bride-to-be would have been judged on her knowledge of tribal symbols and her skill in depicting them. She would have had her mother's weavings for inspiration, so her carpets may have looked almost identical to those her mother had woven some fifteen to thirty years earlier. Making new carpets for the home was an important ritual for each marriage and generation. The more isolated the family group, the less likely external influence should come to bear on the designs, slowing development and change in pattern. Changes in traditional patterns would probably have come about due to marriages between different groups or exposure to the weavings of others.

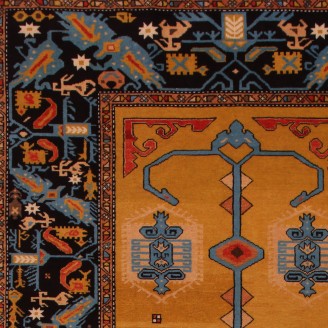

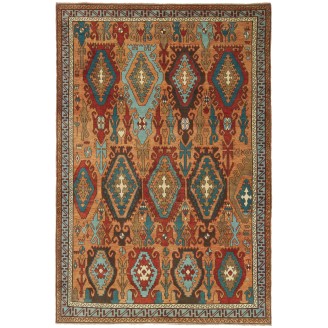

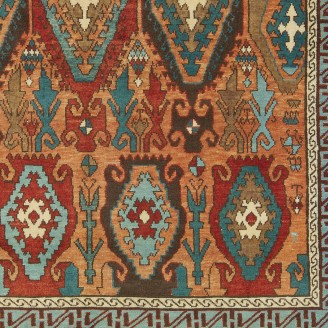

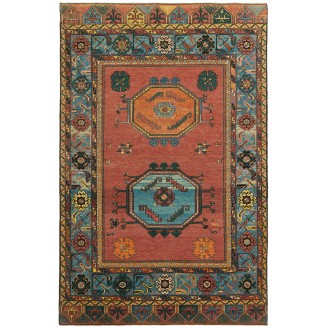

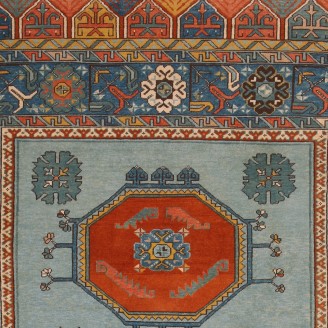

Anatolian Patterns

Anatolian Patterns A "Bellini type" Anatolian Islamic prayer rug, seen from the top, at the feet of the Virgin Mary, in Gentile Bellini's Madonna and Child Enthroned, late 15th century.

A "Bellini type" Anatolian Islamic prayer rug, seen from the top, at the feet of the Virgin Mary, in Gentile Bellini's Madonna and Child Enthroned, late 15th century.One aspect of nomadic pastoralist life that we can be certain about is that it did not allow for many possessions. The baggage that the tribes carried from place to place comprised only necessities, including carpets and kilims - for warmth, storage, and decoration. Carpets were primarily functional objects, but the addition of pattern and color allowed them to represent the art of their particular group. This was the art of women and an important medium of artistic expression.

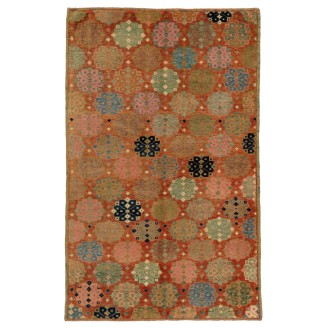

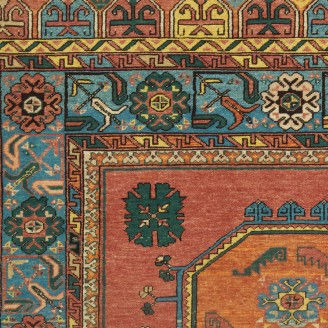

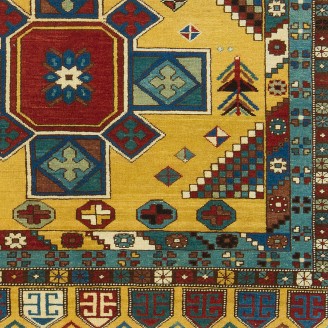

Traditional dyes used for Anatolian carpets are obtained from plants, insects, and minerals. The Anatolian rug is distinct from carpets of other provenience in its more pronounced use of primary colors. Western Anatolian carpets prefer red and blue colors, whereas Central Anatolians use more red and yellow, with sharp contrasts set in white. Natural dyes used in Anatolian rugs include: Red from Madder (Rubia tinctorum) roots, Yellow from plants, including onion (Allium cepa), several chamomile species (Anthemis, Matricaria chamomilla), and Euphorbia, Black: Oak apples, Oak acorns, Tanner's sumach, Green by double dyeing with Indigo and yellow dye, Orange by double dyeing with madder red and yellow dye, Blue: Indigo gained from Indigofera tinctoria.

Anatolian rugs are most often tied with symmetrical knots, which were so widely used in the area that Western rug dealers in the early 20th century adopted the term "Turkish" or "Ghiordes" knot for the technique. From the 1870s onwards, the Ottoman court manufacturers also produced silk-piled rugs, sometimes with inwoven threads of gold or silver. Still, the traditional material of most Anatolian rugs was hand-spun, naturally dyed wool.

Sheep's wool is the most frequently used pile material in a Turkish rug because it is soft, durable, easy to work with, and not too expensive. It is less susceptible to dirt than cotton, does not react electrostatically, and insulates against both heat and cold. This combination of characteristics is not found in other natural fibers. The wool comes from the coats of sheep. Natural wool comes in white, brown, fawn, yellow, and gray colors, which are sometimes used directly without going through a dyeing process. Sheep's wool also takes dyes well. Traditionally, wool used for Turkish carpets is spun by hand. Before the yarn can be used for weaving, several strands must be twisted together for additional strength.

Photo: Anatolian Rug Weaving, 2021 Gaziantep

Photo: Anatolian Rug Weaving, 2021 Gaziantep