-409x600fit.jpg)

Carpets of Middle-Eastern origin, either from Anatolia, Persia, Armenia, Levant, the Mamluk state of Egypt, or Northern Africa, were used as decorative features in Western European paintings from the 14th century onwards. More depictions of Oriental carpets in Renaissance paintings survive than actual carpets contemporary with these paintings. Few Middle-Eastern carpets produced before the 17th century remain, though the number of these known has increased in recent decades. Therefore, from its onset in the late 19th century, comparative art-historical research relied on carpets represented in datable European paintings.

Activities of scientists and collectors beginning in the late 19th century have substantially increased the corpus of surviving Oriental carpets, allowing for a more detailed comparison of existing carpets with their painted counterparts. Western comparative research resulted in an ever more detailed cultural history of the Oriental art of carpet weaving. This has renewed and inspired the scientific interest in their countries of origin. Comparative research based on Renaissance paintings and carpets preserved in museums and collections continues to contribute to the expanding body of art historical and cultural knowledge.

The tradition of precise realism among Western painters of the late 15th and 16th centuries provides pictorial material that is often detailed enough to justify conclusions about even minute details of the painted carpet. The carpets are treated with exceptional care in the rendering of colors, patterns, and details of form and design: The painted texture of a rug depicted in Petrus Christus's Virgin and Child, the drawing of the individual patterns and motifs, and the way the pile opens where the carpet is folded over the steps, all suggest that the depicted textile is a pile-woven carpet.

.jpg) A "Bellini type" Islamic prayer rug, seen from the top, at the feet of the Virgin Mary, in Gentile Bellini's Madonna and Child Enthroned, late 15th century.

A "Bellini type" Islamic prayer rug, seen from the top, at the feet of the Virgin Mary, in Gentile Bellini's Madonna and Child Enthroned, late 15th century.

Prayer rug, Anatolia, late 15th to early 16th century, with "re-entrant" keyhole motif.

Prayer rug, Anatolia, late 15th to early 16th century, with "re-entrant" keyhole motif.

.jpg) Hans Memling's Still Life with a Jug with Flowers, late 15th century.

Hans Memling's Still Life with a Jug with Flowers, late 15th century.

MODEL: ART00438 Memling Gul Kazak Rug

MODEL: ART00438 Memling Gul Kazak Rug

Visually, the carpets draw attention to an important person or highlight a location where significant action is going on. In parallel with the development of Renaissance painting, initially, mainly Christian saints and religious scenes are set out on the carpets. Later on, the carpets were integrated into secular contexts but always represented the idea of opulence, exoticism, luxury, wealth, or status. First, their use was reserved for the most powerful and most wealthy, for royalty and nobility. Later, as more people gained sufficient wealth to afford luxury goods, Oriental carpets appeared on the portraits of merchants and wealthy burghers. During the late 17th and 18th centuries, the interest in depicting carpets declined. In parallel, the paintings pay less attention to detail.

The richly designed Oriental carpets appealed strongly to Western painters. The rich and various colors may have influenced the great Venetian painters of the Quattrocento. It has been suggested that the pictorial representation of carpets is linked to the development of the linear perspective, which was first described by Leon Battista Alberti in 1435.

The depiction of Oriental carpets in Renaissance paintings is regarded as an important contribution to a "world history of art", based upon interactions of different cultural traditions. Rugs from the Islamic world arrived in large numbers in Western Europe by the 15th century, which is increasingly recognized as a pivotal temporal nexus in the cultural encounters that contributed to the development of Renaissance ideas, arts, and sciences. Intensified contacts, especially the increasing trade between the Islamic world and Western Europe, have provided material sources and cultural influences to Western artists during the centuries to come. In turn, European market demands also affected carpet production in their countries of origin.

Domenico di Bartolo's The Marriage of the Foundlings features a large carpet with a Chinese-inspired phoenix-and-dragon pattern, 1440.

Domenico di Bartolo's The Marriage of the Foundlings features a large carpet with a Chinese-inspired phoenix-and-dragon pattern, 1440.

Phoenix-and-dragon carpet, first half or middle of the 15th century, Berlin.

Phoenix-and-dragon carpet, first half or middle of the 15th century, Berlin.

,_madonna_del_latte,_1340-50_ca.jpeg) Lippo Memmi's Virgin Mary and Child features an "animal carpet" with two opposed birds beside a tree, 1340-50.

Lippo Memmi's Virgin Mary and Child features an "animal carpet" with two opposed birds beside a tree, 1340-50.

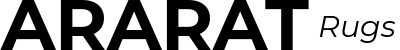

Anatolian animal carpet, circa 1500, found in Marby Church, Sweden.

Anatolian animal carpet, circa 1500, found in Marby Church, Sweden.

In 1871, Julius Lessing published his book on Oriental carpet design. He relied more on European paintings than on the examination of actual carpets for lack of material because ancient Oriental carpets were not yet collected at the time when he worked on his book. Lessing's approach has proven very useful in establishing a scientific chronology of Oriental carpet weaving, and was further elaborated and expanded mainly by scholars of the "Berlin school" of History of Islamic art: Wilhelm von Bode, and his successors Friedrich Sarre, Ernst Kühnel, and Kurt Erdmann developed the "ante quem" method for the dating of oriental carpets based on Renaissance paintings.

These art historians were also aware of the fact that their scientific approach was biased: Only carpets produced by manufactories were exported to Western Europe, and consequently were available to the Renaissance artists. Village or nomadic rugs did not reach Europe during the Renaissance and were not depicted in paintings. Not until the mid-twentieth century, when collectors like Joseph V. McMullan or James F. Ballard recognized the artistic and art historic value of village or nomadic carpets, were they appreciated in the Western World.

Carpet Patterns Named After Artists;

When Western scholars explored the history of Islamic carpetmaking, several types of carpet patterns became conventionally called after the names of European painters who had used them, and these terms remain in use. The classification is mostly that of Kurt Erdmann, once Director of the Museum für Islamische Kunst (Berlin), and the leading carpet scholar of his day. Some of these types ceased to be produced several centuries ago, and the location of their production remains uncertain, so obvious alternative terms were not available. The classification ignores the border patterns and distinguishes between the type, size, and arrangement of gul, or larger motifs in the central field of the carpet. In addition to four types of Holbein carpets, there are Bellini carpets, Crivellis, Memlings, and Lotto carpets. These names are somewhat random: many artists painted these types, and single artists often painted many types of carpets.

Bellini Carpets

Both Giovanni Bellini and his brother Gentile (who visited Istanbul in 1479) painted examples of prayer rugs with a single "re-entrant" or keyhole motif at the bottom of a larger figure traced in a thin border. At the top end, the borders close diagonally to a point, from which hangs down a "lamp". The design had Islamic significance, and its function seems to have been recognized in Europe, as they were known in English as "musket" carpets, a corruption of "mosque". In the Gentile Bellini seen at the top, the rug is the "right" way round; often this is not the case. Later Ushak prayer rugs where both ends have the diagonal pointed inner border, as at the top only of Bellini rugs, are sometimes known as "Tintoretto" rugs, though this term is not as commonly used as the others mentioned here.

Lorenzo Lotto's Husband and Wife, 1523, with a "Bellini" carpet showing the keyhole re-entrant motif.

Lorenzo Lotto's Husband and Wife, 1523, with a "Bellini" carpet showing the keyhole re-entrant motif.

Re-entrant prayer rug, Anatolia, late 15th to early 16th century.

Re-entrant prayer rug, Anatolia, late 15th to early 16th century.

Carlo Crivelli's Annunciation with St Emidius, 1486, with Crivelli carpet in the upper left corner. See enlarged detail at left. Note that there is a second, different carpet at the top center.

Carlo Crivelli's Annunciation with St Emidius, 1486, with Crivelli carpet in the upper left corner. See enlarged detail at left. Note that there is a second, different carpet at the top center.

"Crivelli" carpet, Anatolia, late 15th-early 16th century.

"Crivelli" carpet, Anatolia, late 15th-early 16th century.

Crivelli Carpets

Carlo Crivelli twice painted what seems to be the same small rug, with the center taken up with a complex sixteen-pointed star motif made up of several compartments in different colors, some containing highly stylized animal motifs. Comparable actual carpets are extremely rare, but there are two in Budapest. The Annunciation of 1482 in the Städel Museum in Frankfurt shows it at the top, and the same carpet seems to be used in the Annunciation, with Saint Emidius in the National Gallery, London (1486), which shows the type hung over a balcony to the top left, and a different type of carpet over another balcony in the right foreground. These seem to be a transitional type between the early animal-pattern carpets and later purely geometrical designs, such as the Holbein types, perhaps reflecting increased Ottoman enforcement of Islamic aniconism.

Memling Carpets

These are named after Hans Memling, who painted several examples of what may have been Armenian carpets in the last quarter of the fifteenth century and are characterized by several lines coming off the motifs that end in "hooks", by coiling in on themselves through two or three 90° turns. Another example appears in a miniature painting for René of Anjou about 1460.

.jpg) Yellow Oriental Carpet in Hans Memling altarpiece of 1488–1490. The "hooked" motif defines a "Memling carpet". Louvre Museum.

Yellow Oriental Carpet in Hans Memling altarpiece of 1488–1490. The "hooked" motif defines a "Memling carpet". Louvre Museum.

Konya 18th century carpet with Memling gul design.

Konya 18th century carpet with Memling gul design.

The Somerset House Conference, with a small-pattern Holbein carpet.

The Somerset House Conference, with a small-pattern Holbein carpet.

Small-pattern Holbein carpet, Anatolia, 16th century.

Small-pattern Holbein carpet, Anatolia, 16th century.

Holbein Carpets

These are seen in paintings from many decades earlier than Holbein, and are sub-divided into four types (of which Holbein only painted two); they are the commonest designs of Anatolian rug seen in Western Renaissance paintings and continued to be produced for a long period of. All are purely geometric and use a variety of arrangements of lozenges, crosses, and octagonal motifs within the main field. The sub-divisions are between; Type I: Small-pattern Holbein. This type is defined by an infinite repeat of small patterns, with alternating rows of octagons and staggered rows of diamonds, as seen in Holbein the Younger's Portrait of Georg Gisze (1532), or the Somerset House Conference (1608). Type II: now more often called Lotto carpets - see below. Type III: Large-pattern Holbein. The motifs in the field inside the border consist of one or two large squares filled with octagons, placed regularly, and separated from each other and the borders by narrow stripes. There are no secondary "gul" motifs. The carpet in Holbein's The Ambassadors is of this type. Type IV: Large-pattern Holbein. Large, square, star-filled compartments are combined with secondary, smaller squares containing octagons or other "gul" motifs. In contrast to the other types, which only contain patterns of equal scale, the type IV Holbein shows subordinate ornaments of unequal scale.

Lotto Carpets

These were previously known as "small-pattern Holbein Type II", but he never painted one, unlike Lorenzo Lotto, who did so several times, though he was not the first artist to show them. Lotto is also documented as owning a large carpet, though its pattern is unknown. They were primarily produced during the 16th and 17th centuries along the Aegean coast of Anatolia, but also copied in various parts of Europe, including Spain, England, and Italy. They are characterized by a lacy arabesque, usually in yellow on red ground, often with blue details.

Though they look very different from Holbein Type I carpets, they are a development of the type, where the edges of the motifs, nearly always in yellow on a red ground, take off in rigid arabesques somewhat suggesting foliage and terminating in branched palmettes. The type was common and long-lasting, and is also known as "Arabesque Ushak".

To judge from paintings, they reached Italy by 1516, Portugal about a decade later, and northern Europe, including England, by the 1560s. They continue to appear in paintings until about the 1660s, especially in the Netherlands.

The Alms of St. Anthony by Lorenzo Lotto, 1542, with two magnificent Oriental carpets, the one in the foreground the type for the Lotto carpet, the other a "para-Mamluk".

The Alms of St. Anthony by Lorenzo Lotto, 1542, with two magnificent Oriental carpets, the one in the foreground the type for the Lotto carpet, the other a "para-Mamluk".

Western Anatolia knotted wool "Lotto carpet", 16th century, Saint Louis Art Museum.

Western Anatolia knotted wool "Lotto carpet", 16th century, Saint Louis Art Museum.

Domenico Ghirlandaio: Madonna and Child enthroned with Saint, circa 1483

Domenico Ghirlandaio: Madonna and Child enthroned with Saint, circa 1483

West Anatolian ‘Ghirlandaio’ rug, late 17th century

West Anatolian ‘Ghirlandaio’ rug, late 17th century

Ghirlandaio Carpets

A carpet closely related to the 1483 painting by Domenico Ghirlandaio was found by A. Boralevi in the Evangelical church, Hâlchiu (Heldsdorf) in Transylvania, attributed to Western Anatolia, and dated to the late 15th century.

The general design of the Ghirlandaio type, as in the 1486 painting, is related to Holbein Type 1. It is defined by one or two central medallions of diamond shape, consisting of an octagon within a square, from whose sides triangular, curvilinear patterns arise. Carpets with this medallion have been woven in the Western Anatolian region of Çanakkale since the 16th century. A carpet fragment with a Ghirlandaio medallion was found in the Divriği Great Mosque, and dated to the 16th century. Carpets with similar medallions were dated to the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, respectively, and are still woven in the Çanakkale region today.

In his essay on "Centralized Designs", Thompson relates the central medallion pattern of oriental carpets to the "lotus pedestal" and "cloud collar (yun chien)" motifs, used in the art of Buddhist Asia. The origin of the design thus dates back to pre-Islamic times, probably Yuan time China. Brüggemann and Boehmer further elaborate that it might have been introduced to Western Anatolia by the Seljuk, or Mongol invaders in the 11th or 13th century. In contrast to the manifold variation of patterns seen in other carpet types, the Ghirlandaio medallion design has remained largely unaltered from the 15th to the 21st century and thus exemplifies an unusual continuity of a woven carpet design within a specific region.

Specific Carpet Types;

Mamluk and Ottoman Cairene Carpets

From the middle of the 15th century onwards, a type of carpet was produced in Egypt which is characterized by a dominant central medallion, or three to five medallions in a row along the vertical axis. Numerous smaller ornaments are placed around the medallions, such as eight-pointed stars, or small ornaments composed of stylized floral elements. The innumerable small geometric and floral ornaments give a kaleidoscopic impression. Sixty of these carpets were given to the English cardinal Thomas Wolsey in exchange for a license for Venetian merchants to import wine to England. The earliest known painting representing a Mamluk carpet is Giovanni Bellini's Portrait of the Doge of Venice Loredan and his four advisers from 1507. A French master depicted The Three De Coligny brothers in 1555. Another representation can be found in Ambrosius Frankens The Last Supper, about 1570. The large medallion is depicted in a way that it forms the nimbus of the head of Christ. The characteristic Mamluk carpet ornaments are visible. Ydema has documented a total of sixteen dateable representations of Mamluk carpets.

After the 1517 Ottoman conquest of the Mamluk Sultanate in Egypt, two different cultures merged, as is seen on Mamluk carpets woven after this date. After the conquest of Egypt, the Cairene weavers adopted an Ottoman-Turkish design. The production of these carpets continued in Egypt into the early 17th century. A carpet of the Ottoman Cairene type is depicted in Ludovicus Finsonius' painting The Annunciation. Its border design and guard borders are the same as the carpet in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. A similar carpet has been depicted by Adriaen van der Venne in Geckie met de Kous, 1630. Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel's The Elders Christ in the House of Mary and Martha, 1628, shows the characteristic S-stems ending in double sickle-shaped lancet leaves. Various carpets of the Ottoman Cairene type are depicted in Moretto da Brescia's frescoes in the "Sala delle Dame" at the Palazzo Salvadego in Brescia, Italy.

_-_The_Last_Supper (2).jpg) Ambrosius Francken, The Last Supper, 16th century, Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, with an Egyptian Mamluk carpet

Ambrosius Francken, The Last Supper, 16th century, Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, with an Egyptian Mamluk carpet

The "Baillet-Latour" Mamluk carpet, Cairo, early 16th century

The "Baillet-Latour" Mamluk carpet, Cairo, early 16th century

Louis Finson, The Annunciation. 17th century, Museo del Prado, depicting an Ottoman Cairene carpet

Louis Finson, The Annunciation. 17th century, Museo del Prado, depicting an Ottoman Cairene carpet

Ottoman Cairene carpet, 16th century, Museum für angewandte Kunst Frankfurt St. 136

Ottoman Cairene carpet, 16th century, Museum für angewandte Kunst Frankfurt St. 136

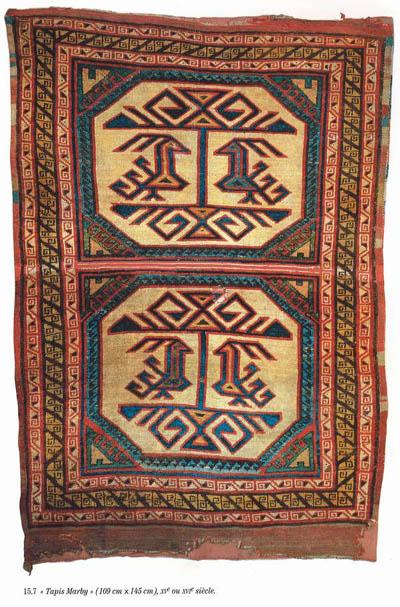

"Chequerboard" or Compartment Carpets from the 17th Century

An extremely rare group of carpets, "chequerboard" carpets were assumed to be a later and derivative continuum of the Mamluk and Ottoman Cairene group of carpets. Only about 30 of these carpets survived. They are distinguished by their design composed of rows of squares with triangles in each corner enclosing a star pattern. All "chequerboard" carpets have borders with cartouches and lobed medallions. Their attribution is still under debate. The colors and patterns resemble those seen in Mamluk carpets; however, they are "S-spun" and "Z-twisted" and thus similar to early Armenian carpets. Since the early days of carpet science, they are attributed to Damascus. Pinner and Franses champion this attribution because Syria was part first of the Mamluk, later of the Ottoman Empire at that time. This would explain the similarities with the colors and patterns of the Cairene carpets. The current dating of the "chequerboard" carpets is also consistent with European collection inventories from the early 17th century. Carpets of the "chequerboard" type are depicted in Pietro Paolini's (1603−1681) Self-portrait, as well as in Gabriël Metsu's painting The Musical Party.

Pietro Paolini's Self-portrait with Chessboard Rug, c.1650

Pietro Paolini's Self-portrait with Chessboard Rug, c.1650

MODEL: ART00200 Chessboard Carpet

MODEL: ART00200 Chessboard Carpet

Gabriël Metsu's, A Musical Party , 1659

Gabriël Metsu's, A Musical Party , 1659

'Chessboard' Carpet, late 16th–early 17th century, MET Museum

'Chessboard' Carpet, late 16th–early 17th century, MET Museum

Large Ushak (Star and Medallion) Carpets

In contrast to the relatively large number of surviving carpets of this type, relatively few of them are represented in Renaissance paintings.

Star Ushak carpets were often woven in large formats. As such, they represent a typical product of higher organized, town manufacture. They are characterized by large dark blue star-shaped primary medallions in infinite repeat on a red ground field containing a secondary floral scroll. The design was likely influenced by northwest Persian book design, or by Persian carpet medallions. As compared to the medallion Ushak carpets, the concept of the infinite repeat in star Ushak carpets is more accentuated and in keeping with the early Turkish design tradition. Because of their strong allusion to the infinite repeat, the star Ushak design can be used on carpets of various sizes and in many varying dimensions.

Medallion Ushak carpets usually have a red or blue field decorated with a floral trellis or leaf tendrils, ovoid primary medallions alternating with smaller eight-lobed stars, or lobed medallions, intertwined with floral tracery. Their border frequently contains palmettes on a floral and leaf scroll and pseudo-kufic characters.

The best-known representation of a Medallion Ushak was painted in 1656 by Vermeer in his painting The Procuress. It is placed horizontally; the upper or lower end with the star-shaped corner medallion can be seen. Under the woman's hand which holds the glass, a part of a characteristic Ushak medallion can be seen. The carpet is seen in Vermeer's The Music Lesson, Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, and The Concert hardly show any differences in the details of the design or the weaving structure indicating that all three pictures might trace back to one single carpet Vermeer might have had at his studio. The paintings by Vermeer, Steen, and Verkolje depict a special type of Ushak carpet of which no surviving counterpart is known. It is characterized by its rather sombre colors, coarse weaving, and patterns with a more degenerated curvilinear design.

Paris Bordone, Presentation of the ring to the Doge of Venice, 1534. The only depiction of a large Star Ushak carpet with eight-pointed star medallions.

Paris Bordone, Presentation of the ring to the Doge of Venice, 1534. The only depiction of a large Star Ushak carpet with eight-pointed star medallions.

_-_WGA24652.jpg) Johannes Vermeer, The Music Lesson (detail), 1662–5, Buckingham Palace

Johannes Vermeer, The Music Lesson (detail), 1662–5, Buckingham Palace

Johannes Vermeer, The Concert, 1663–6, stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, in 1990

Johannes Vermeer, The Concert, 1663–6, stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, in 1990

.jpg) Jan and Nikolaas Verkolje, Portrait of Willem de Vlamingh, 1690–1700

Jan and Nikolaas Verkolje, Portrait of Willem de Vlamingh, 1690–1700

Persian and Anatolian Carpets in the 17th Century

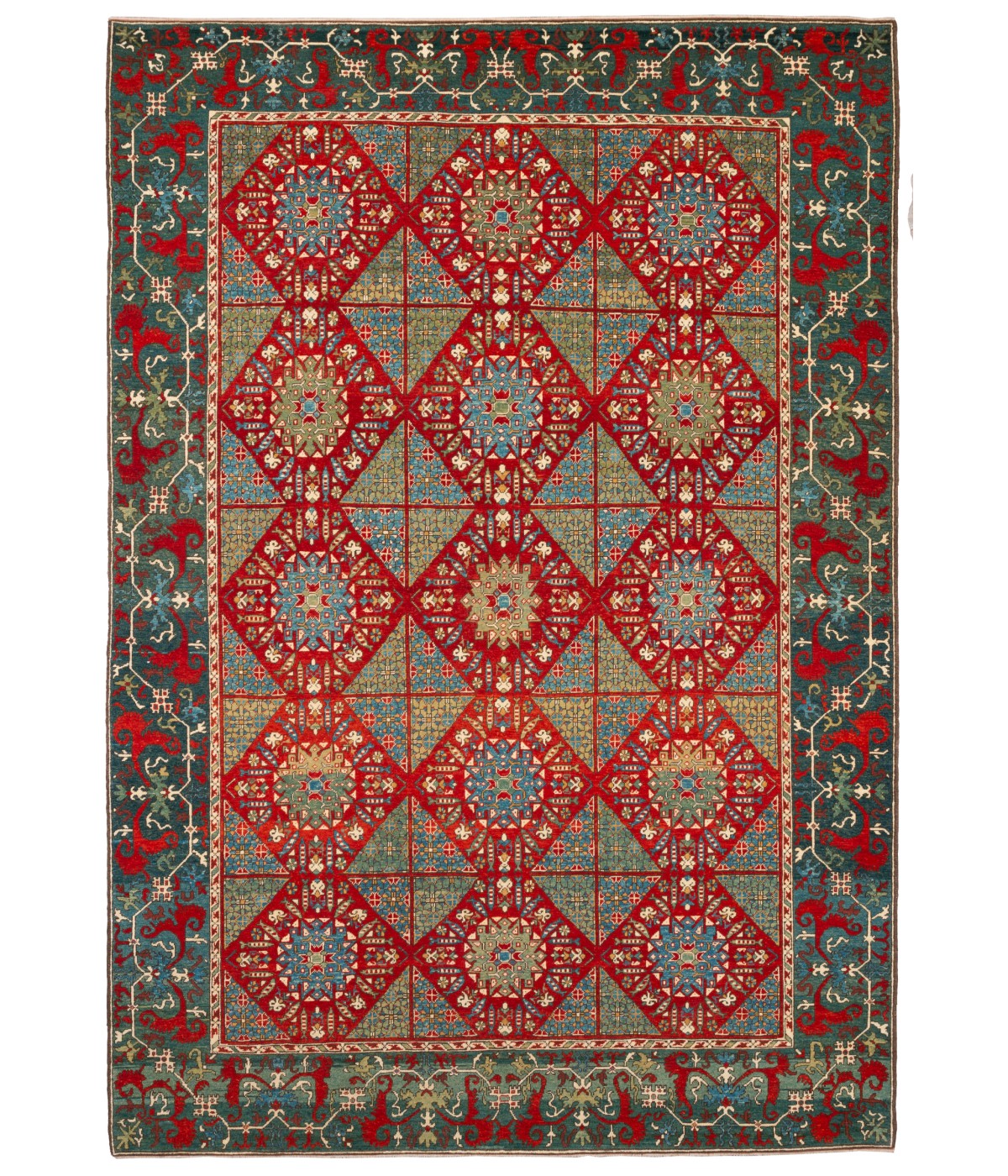

Carpets remained an important way of enlivening the background of full-length portraits throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, for example in the English portraits of William Larkin.

The finely-knotted silk carpets woven in the time of Shah Abbas I at Kashan and Isfahan are rarely represented in paintings, as they were doubtless very unusual in European homes; however, A Lady playing the Theorbo by Gerard Terborch (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 14.40.617) shows such a carpet laid upon the table on which the lady's cavalier is sitting. Floral "Isfahan" carpets of the Herat type, on the other hand, were exported in great numbers to Portugal, Spain, and the Netherlands, and are often represented in interiors painted by Velásquez, Rubens, Van Dyck, Vermeer, Terborch, de Hooch, Bol and Metsu, where the dates established for the paintings provide a yardstick for establishing the chronology of the designs.

Anthony van Dyck's royal and aristocratic subjects had mostly progressed to Persian carpets, but less wealthy sitters are still shown with the Turkish types. The 1620 Portrait of Abraham Graphaeus by Cornelis de Vos, Thomas de Keyser's Portrait of an unknown man (1626), and Portrait of Constantijn Huyghens and his clerk (1627) are amongst the earliest paintings depicting a new type of Ottoman Turkish manufactory carpet, which was exported to Europe in large quantities, probably to meet the increasing demand. A large number of similar carpets were preserved in Transylvania, which was an important center of the Armenian carpet trade during the 15th–19th century. Many Armenians left their homes in Western Armenia ruled by Ottoman Turkey and founded craft centers of carpet weaving in Gherla, Transylvania. Hence, carpets of this type are known by a term of convenience as "Transylvanian carpets". Pieter de Hooch's 1663 painting Portrait of a Family Making Music depicts an Ottoman prayer rug of the "Transylvanian" type. In the American colonies, Isaac Royall and his family were painted by Robert Feke in 1741, posed around a table spread with a Bergama rug.

From the mid-century European direct trade with India brought Mughal versions of Persian patterns to Europe. Painters of the Dutch Golden Age showed their skill through the depiction of light effects on table carpets, like Vermeer in his Music Lesson (Royal Collection). By this date, they have become common in the homes of the reasonably well-to-do, as is shown by historical documentation of inventories. Carpets are sometimes depicted in scenes of debauchery from the prosperous Netherlands.

By the end of the century, Oriental carpets had lost much of their status as prestige objects, and the grandest sitters for portraits were more likely to be shown on the high-quality Western carpets, like Savonneries, now being produced, whose less intricate patterns were also easier to depict in a painterly manner. Several Orientalist European painters continued to accurately depict Oriental carpets, now usually in Oriental settings.

Pieter de Hooch: Portrait of a Family Making Music, 1663, Cleveland Museum of Art

Pieter de Hooch: Portrait of a Family Making Music, 1663, Cleveland Museum of Art

"Transylvanian" type prayer rug, 17th century, National Museum, Warsaw

"Transylvanian" type prayer rug, 17th century, National Museum, Warsaw

William Larkin's Dorothy Cary, later Viscountess Rochford, 1614–8, Kenwood House. Anatolian "animal-style" carpet with a more developed design.

William Larkin's Dorothy Cary, later Viscountess Rochford, 1614–8, Kenwood House. Anatolian "animal-style" carpet with a more developed design.

Thomas de Keyser: Portrait of Constantijn Huygens and his clerk, 1627, National Gallery

Thomas de Keyser: Portrait of Constantijn Huygens and his clerk, 1627, National Gallery