The Museum for Islamic Art in Berlin boasts one of the highest-quality carpet collections in the world and is a center for international research and scientific conservation. The Museum's leading position results from over 100 years of research and collecting.

The art historian and museum expert Wilhelm von Bode [1845-1929] was one of the first major collectors of oriental carpets in the modern period. When he donated his carpet collection to the newly established Islamic Art Department of Berlin's Royal Collections in 1905, he helped to realize his dream by establishing the founding collection of today's Museum for Islamic Art. At that time, he also countered popular opinion that Islamic art provided a mere model for German arts and crafts. Bode instead championed the close connections between European and Islamic art, an idea that still resonates today.

Many carpets were destroyed during The Second World War. The employees' passion and willpower to save and rebuild the carpet collection subsequently challenged the trauma. This room presents the history, conservation practice, and development of the Museum for Islamic Art's carpet collection.

-As I conclude my journey through the carpets of the Museum of Islamic Art in Berlin, I am left with a profound appreciation for the intricate beauty and cultural significance of these timeless artifacts. The carpets, with their rich history and symbolic designs, serve as a testament to the enduring legacy of Islamic art. A visit to this museum is not just a walk through its halls; it's a voyage through centuries of artistic expression, craftsmanship, and cultural exchange, all woven into the delicate fibers of these extraordinary carpets.’ -Hakan KARAR

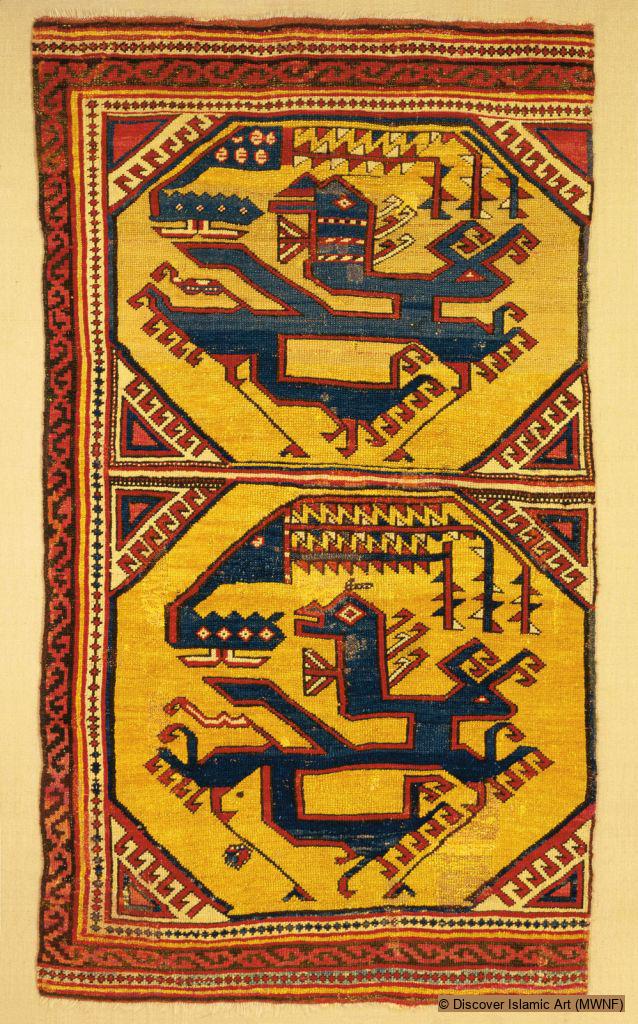

ART00248 The Bode-Angeli Niche with Cloudbands Rug in the Museum

This carpet is among the most famous in the Berlin collection. As early as 1871, it was acquired by Wilhelm von Bode for the painter Heinrich von Angeli, but it was not until 1905 that Bode could buy it from his heirs and donate it to the Museum. Von Angeli and some of his colleagues depicted this carpet several times. The charm of this carpet lies in its depth of color, its high, dense pile, and the impressive sheen of the wool. On a dark blue ground, two red-ground spandrels are separated in the form of niches by a solid white line. Unusually, the spandrels blend into each other at their tops. The lower half of the niche field is filled with a light blue cloud band, in whose arc a large blossom forms a fixed point. This cloud band is reminiscent of delimitations in the so-called keyhole or Bellini carpets. Their often angular arch forms are associated with fountains, which were needed for the ritual cleansing before prayer. Because of the blossoms' Persian appearance, the cloud band's origin from East Asian cultures, and the use of depressed warps, this carpet has occasionally been ascribed to Persia. However, not only the color palette and the reference to the keyhole motif but also the use of a symmetrical knot speak in favor of a location in Turkey.

Medallion Ushak Carpet in the Museum:

This 17th-century medallion carpet is from central Anatolia, circa 1500-1550. The town of Ushak, north of Denizli, is probably one of the most important and renowned carpet centers. Carpets have survived from the 16th century and can be seen in several museums. In the 17th century, significant quantities of Ushak carpets were made for the royal houses of Europe, often incorporating crests; many Christian churches, not only in Transylvania, were frequently decorated with giant pieces. According to their structure and patterning, there are several types of Ushak carpets: the star Ushak, the medallion Ushak, the 'bird' carpet (with a white background, the name relates to the shapes of the field motifs), and 'Chintamani' carpets (often with a white background and three-ball pattern, primarily in connection with cloud bands).

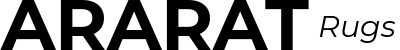

Dragon and Phoenix Carpet in the Museum:

This fragmented carpet is one of the most critical animal carpets of the early Ottoman period that have become known to the present day. Two highly stylized animals, a dragon, and a phoenix, fight against a yellow background within two octagonal spaces. The phoenix is swooping down onto the dragon from above. The image is more transparent in the lower octagonal casing than in the upper. The outer border is composed of semi-palmette tendrils framed on both sides by an edging of little rosettes. The original border appears missing on both the left and right sides. It is possible that the carpet was originally more expansive in shape, featuring a more significant number of octagonal compartments. This would make it more akin to the animal carpets reproduced in paintings. The dragon and phoenix motif, which originated in China – where yellow was considered to be the color of the sovereign – was introduced into Islamic art in the AH 7th / AD 13th century with the arrival of the Mongols, as is demonstrated by its ubiquitous presence on several works of art, made in a variety of materials.

Cairene Ottoman Carpet in the Museum:

This wool carpet presents a large border with repeating large blossoms, framing an extensive surface decorated with repeating chintamanis, the pearl-like spots that were popular in the Ottoman court. A circular medallion occupies the center, with a fleur-de-lis-like motif at its top and bottom, forming a vertical axis. The design of a central medallion and four corner quarter-medallions is thought to have originated in decorative book bindings. While displaying a Turkish design, the technique and materials of this carpet are Egyptian—reflecting the presence of Egyptian carpet weavers in sixteenth-century Ottoman workshops. A so-called 'thunder-and-lightening' symbol covers the entire field of this rug. Against this background appear a single, scalloped central medallion and four corner pieces. The borders are of particular interest. The main border has a dual meandering scroll, one beset with rosettes, the other with palmette blossoms.

ART00147 Mamluk Prayer Rug in the Museum

This carpet demonstrates through its design that it belongs to the group of prayer rugs. The inner area is adorned with a red-colored arch-shaped mihrab (prayer niche). Placed in front of the niche is a basin, seen from above, from which a small tree with green leaves is rendered in a semi-abstract design with fine lines. A small yellow jug with a handle and short spout has been incorporated into the tree's center. This jug may relate to Sura 5, verse 8 of the Qur'an, which mentions the obligation of ablutions to be undertaken before prayer. Green-coloured, eight-pointed plaited stars can be seen in the corners of the mihrab arch. Above the mihrab is a rectangular space filled with palms and cypresses. Two borders frame the inner area. A decorative cloud motif band fills the thinner border. This cloud-motif band has been a common feature of Ottoman art since the AH 9th and 10th / AD 15th and 16th centuries, and it originated in China. On this rug, the yellow cloud motif bands are displayed over a red background and are positioned very close to one another. The rug's wider border consists of a continuous tendril-like interlacing band involving plant motifs over a light-green background.