The Islamic carpets in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) represent a magnificent collection of textile art from the Islamic world. Spanning several centuries and regions, this collection showcases the rich tradition of carpet weaving in Islamic societies. From intricate geometric patterns to lush floral designs, the carpets exhibit a variety of styles and techniques that reflect the cultural heritage and craftsmanship of their regions of origin. The collection includes carpets used for daily life and luxurious pieces commissioned by royalty and the elite. Each piece tells a story, offering a fascinating glimpse into carpets' history, artistry, and cultural significance in the Islamic world.

“In this blog post, I want to give you information about the Islamic carpets in the Metropolitan Museum and McMullan’s book ‘Islamic Carpets’. This book has a memory for me; many years ago, I bought this book at a very high price and did a lot of design work related to the carpets inside. I had the opportunity to bring many carpets back to life. When I found another copy of the book at a more affordable price, I bought it as well, so I have two copies in my collection. With Walter B. Denny’s How to Read Islamic Carpets (2014) Book, these are another unique resources that should be in your reference book archive.” -Hakan KARAR

'Islamic Carpets' with this authoritative and comprehensive volume by Joseph McMullan, published by the Near Eastern Art Research Center, New York, U.S.A. First released in 1965 and featuring selections from the Metropolitan Museum of Art's esteemed collection, this meticulously researched and elegantly designed book is a seminal resource for scholars, collectors, and enthusiasts of Islamic art, culture, and history. McMullan unfolds the historical evolution, craftsmanship, and symbolism of carpets across the Islamic world, revealing the rich narratives intricately woven into each piece. From the elaborate floral motifs of Persian rugs to the geometric patterns of Central Asia and the Caucasus, each carpet encapsulates a story that reflects the religious beliefs, cultural practices, and artistic sensibilities of the Islamic societies from which they originate.

The book commences with an overview of the historical development of carpet weaving in the Islamic world, tracing its origins, influences, and evolution over time. It then examines the different regional styles, patterns, and techniques, highlighting carpets' distinctive characteristics and unique features from various Islamic regions, including Persia, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. A significant focus of the book is the symbolism embedded within the designs of Islamic carpets. A dedicated section explores the religious, mythological, and cultural motifs that recur in these textiles. From the symbolism of colors to the significance of floral and geometric patterns, the book thoroughly interprets the hidden meanings woven into the fabric of Islamic carpets.

17th-century Vase Carpet – Metropolitan Museum of Art

17th-century Vase Carpet – Metropolitan Museum of Art On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 462

Model: ART00443

Model: ART00443Kerman Vase-Technique Carpet

This carpet overflows with naturalistically rendered flowers and plants, organized around one central medallion and four-quarter medallions in each corner. A similar medallion design can be seen on many decorative leather book covers from the same period, and it is likely that the manuscript design was incorporated into the visual repertoire of Safavid weavers. Artists working in the court atelier produced drawings and designs for artisans in various media. The designs and trends generated by the court were then adopted by commercial workshops that created high-quality carpets like this one.

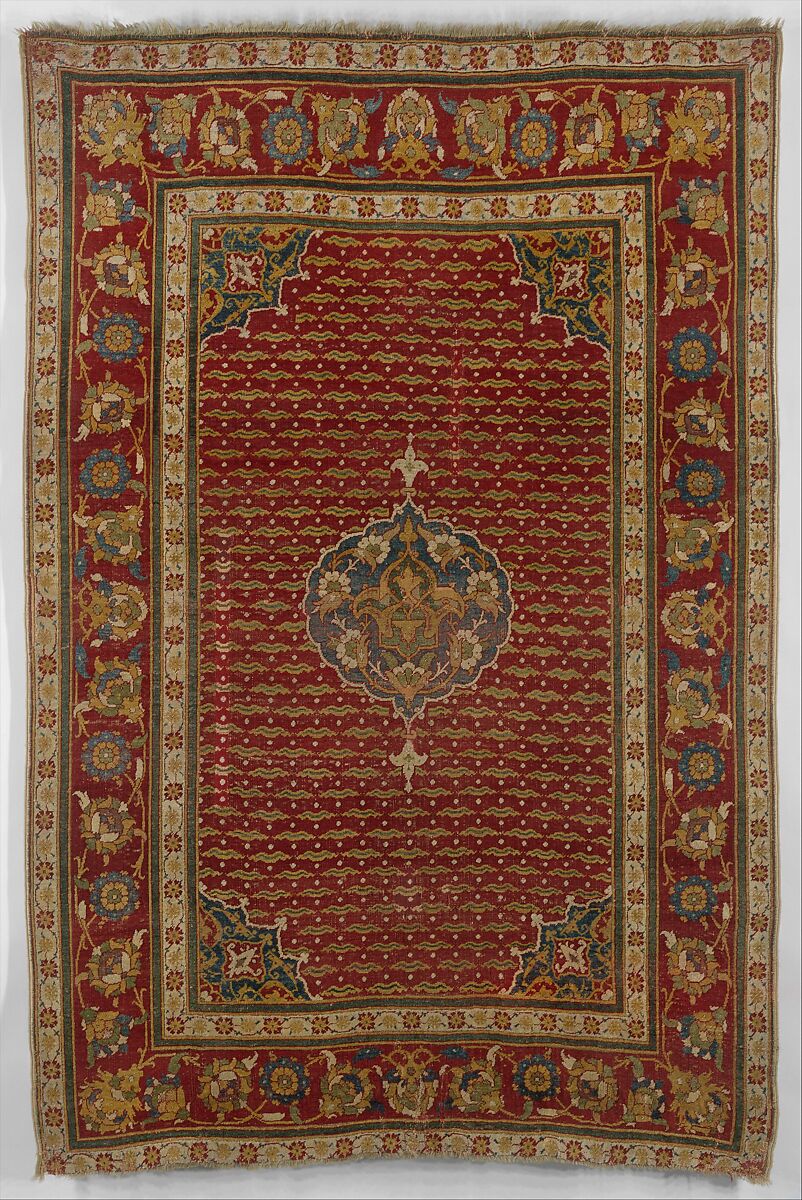

ca 1550, Carpet – Metropolitan Museum of Art

ca 1550, Carpet – Metropolitan Museum of ArtNot on view

Model: ART00565

Model: ART00565Cairene Ottoman Carpet

This wool carpet presents a large border with repeating large blossoms, framing an extensive surface decorated with repeating chintamanis, the pearl-like spots that were popular in the Ottoman court. A circular medallion occupies the center, with a fleur-de-lis-like motif at its top and bottom, forming a vertical axis. The design of a central medallion and four corner quarter-medallions is thought to have originated in decorative book bindings. While displaying a Turkish design, the technique and materials of this carpet are Egyptian—reflecting the presence of Egyptian carpet weavers in sixteenth-century Ottoman workshops.

18th century The 'Nigde' Carpet – Metropolitan Museum of Art

18th century The 'Nigde' Carpet – Metropolitan Museum of ArtOn view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 462

Model: ART00046

Model: ART00046Nigde Carpet

The so-called "Nigde Carpet," one of the most famous Islamic carpets, was allegedly discovered in a mosque in the central Anatolian Nigde but was probably produced in northwest Iran or Transcaucasia. The origins of its design are indisputably Iranian, as is its overall layout of ogival forms. The composition may have been inspired by a silk textile layout, possibly filtered through the production of the ogival-layout rugs woven in Kirman's so-called "vase carpet technique" in the seventeenth century. Although mutated into angular and geometric forms, the essential design elements of sinuous Chinese cloud bands, lotus-flower palmettes, and curved leaves, all part of the rich vocabulary of Safavid carpets, are identifiable in this carpet.

17th-century Carpet – Metropolitan Museum of Art

17th-century Carpet – Metropolitan Museum of ArtNot on view

Model: ART00541

Model: ART00541Cairene Ottoman Carpet

The scalloped horseshoe arch and overall floral field are characteristic of a small group of Ottoman rugs. Some, with all-wool construction, are thought to come from Cairo, a well-established rug-weaving center when it was conquered by the Ottomans in 1517. While continuing the use of the Senneh or Persian knot and limited palette of colors of the geometric patterned carpets made under Mamluk rule, the Cairo weavers employed Ottoman elements in their designs. In the center of the field is a configuration of a rosette-type blossom surrounded by palmettes. This device appears on many non-prayer rugs of the period and may have been adapted from them. The border is unusual for this type of rug and contains Ottoman-favored flowers–tulips, hyacinths, and carnations. The double flowers appearing at the border's top and bottom center may result from a design that was not well-planned. The guard stripe pattern is a popular one appearing on many rugs of this group.

16th-century Fragment of an Ottoman Court Carpet – Metropolitan Museum of Art

16th-century Fragment of an Ottoman Court Carpet – Metropolitan Museum of ArtNot on view

Model: ART00181

Model: ART00181Turkish Court Manufactury Rug - Reinterpreted Rug

Although Mamluk Cairo fell to the Ottomans in 1517, the city remained a major center for artistic production. Using the same materials and techniques as earlier Mamluk carpets, Ottoman court carpets were produced in Egypt for export, primarily to the Ottoman court in Istanbul. The immense scale of this carpet's drawing suggests it once formed part of an even larger carpet.