Arthur Cecil Edwards (1881 – 1953 or 1957) was a dealer in and authority on Persian carpets. He was the managing director of Oriental Carpet Manufacturers based in Turkey. Arthur Edwards was born in Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1881 to Charles Reed Edwards (born London) and Louise Baker (born Constantinople).

Edwards’s uncle, James Baker, founded the Oriental Carpet Manufacturers (OCM) in Smyrna, today’s Izmir, in 1907/1908. The company bought and produced Persian carpets for export to the United Kingdom. As an OCM employee, Edwards moved to Hamadan, north-western, in 1911, where he built and managed his carpet production for the company. He and his wife were fascinated by Persian culture. In 1923, they left Iran, traveled to Pakistan for a few months, and finally went to London. There, Edwards took over the management of the OCM and expanded its business activities in the United States. He also oversaw the outsourcing of carpet production to India to reduce production costs. During the Second World War, the family moved to Oxford and returned to London.

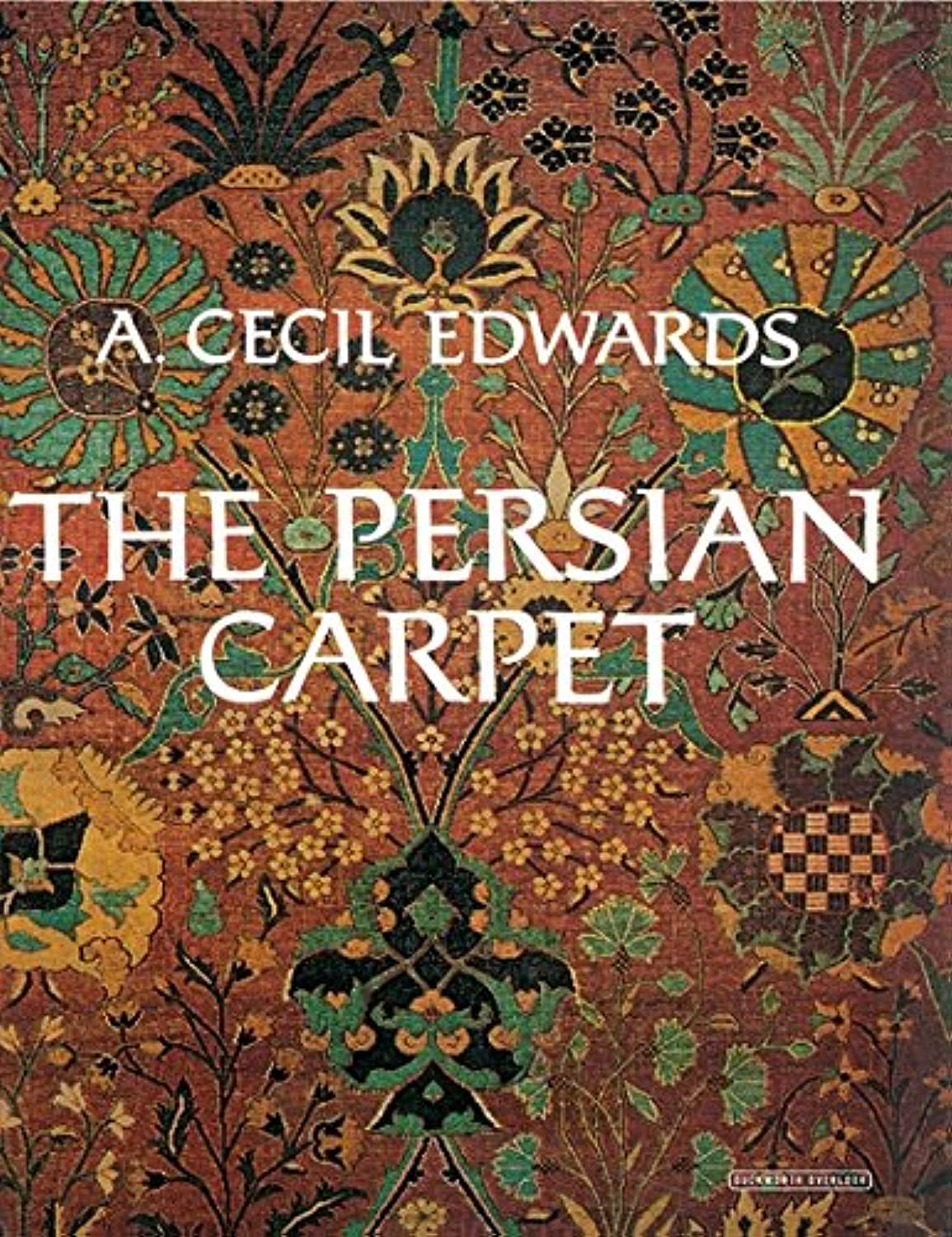

His masterwork was The Persian Carpet (1953), published posthumously and repeatedly reissued. The monograph is still one of the standard works on the Persian carpet. It describes in detail the production, colors, patterns, and stylistic development of the Persian knotted carpet in the different provinces of Iran, as well as the history of the regions, their carpet production, the number of looms, and production figures since the end of the 19th to the middle of the 20th century. It gives an outlook on the future of the carpet industry under the influence of the European market. We would like to share with you his impressions of natural dye usage in Persia in the 1900s;

Until recent years the weavers of the Heriz area procured their wools or spun yarn from the neighbouring Shah- seven tribes. That admirable practice is, unhappily, fast disappearing. Today the villagers buy their yarn ready spun in the bazaars of Tabriz or Ardebil. Most of it is spun from skin wool and is a very different material from the yarn which they formerly procured from the nomad tribesmen. The former was long in the fibre, lustrous and lofty; and when dyed it gave a clear, bright shade. The latter is short in the fibre, dull and springless; and when dyed the shades are often flat or muddy. The system of dyeing, too, has sadly deteriorated. Until the last decade the yarns were dyed in the villages; the blue, red and green by the village dyers; the other shades by the weaver herself in her own pots over her own fire. Both used the excellent, time-honoured technique of their ancestors. Now, alas, the village dyer has disappeared from many of the villages and will soon, I fear, disappear from them all. The blue, red and green are now dyed in Tabriz by the town dyers, with synthetic dyes. The use of natural madder-which for fifty years was the outstanding colour in the carpets from the Heriz area-is disappearing. It is proverbially difficult to induce a dyer- especially a Persian dyer-to reveal his secrets, Many of them still believe (though in recent years this belief has been somewhat shaken) that their ancient formulas are of inestimable value. I realised, therefore, that it would not be an easy matter to discover fromthe Tabriz dyers what method they were using in dyeing the yarn for the Heriz weavers. Happily, I met an old friend-one Amir Ali-who was employed by one of the Tabriz factories. As a member of the guild of dyers he had the entrée to the town dye-houses; to him I explained my dilemma and he agreed to show me round. Before we set out he bade me use my eyes, hold my tongue and listen. I soon discovered that in place of natural madder the Tabriz dyers were using a synthetic alizarine dye of Swiss manufacture. This is the dye which produces the dark, browny-red which I had seen everywhere in the Heriz area. Indeed, the grounds of half the carpets were in this murky, sombre shade. The dyestuff, if properly employed, is fast to light and alkalis. But the shade which it produces is very different from the lighter, warmer red which the village dyers formerly obtained with natural madder. Unhappily, however, the dyestuff is not always properly used. The lighter red, which is employed in the motives (but not as a ground colour), is often dyed without the use of a mordant. The shade is, therefore, fugitive to light and alkalis. This information was imparted with disarming frankness by one Ostad Mohammed, a Tabriz dyer. “It is like this,” said he to my friend Amir Ali. “When a villager asks me to dye this colour” -and he pointed to a hank of lightish red yarn- “I inform him that if he wants a colour that will not fade, the price is 8 tomans a batman; but if he is content with a colour which may perhaps fade a little, the price is 4 tomans. These avaricious villagers appear always to prefer the cheaper method.” “I presume,” suggested my friend Amir Ali, “that in order to meet the inadequate price offered by the parsimonious villagers you have been compelled to readjust your methods-perhaps by omitting the first boiling in alum.” “It is obvious,” replied Ostad Mohammed Ali, “that no dyer could be expected to provide two boilings, one with alum and the second with the dye (to say nothing of a scouring between the two processes), for the miserable price of 4 tomans a batman.” “That would, indeed, be impossible,” agreed my friend Amir Ali. It must, therefore (I fear), be accepted that the Tabriz dyers are in the habit of omitting the mordant from some of the secondary colors which they dye for the weavers from the Heriz area.” - Arthur Cecil Edwards